When organic wheat growers choose a variety, they aren’t just planting seed—they’re planting bread, tortillas, and the reputation of their crop in the marketplace. That’s why milling and baking quality matter as much as yield. Extension Specialists and Wheat Researchers have been digging into an important question for growers: how do milling quality and baking quality fit into variety choice, especially for organic systems? These traits, along with protein and yield, play a direct role in what millers want and what farmers get paid for.

Milling Quality vs. Baking Quality

- Milling quality is about how efficiently a kernel turns into flour. Seed size, uniformity, and hardness all affect milling yield.

- Baking quality is about what happens in the bakery—how dough handles, rises, and produces bread or tortillas that buyers want.

Testing happens at several levels. The Cereal Quality Lab at College Station does preliminary evaluations, while the USDA and Wheat Quality Council conduct full baking and milling trials with multiple mills and bakeries. Every TAM variety is rated, and those scores directly influence variety release decisions.

Variety Highlights for Organic Wheat Growers

TAM 114

Mid-season hard red winter wheat prized for excellent milling and baking quality, solid yield potential, and strong adaptability.

- Strengths: Excellent dough properties, solid straw strength, good grazing ability, drought tolerance, and winterhardiness. Moderately resistant to stripe, leaf, and stem rusts as well as Hessian fly; good acid soil tolerance.

- Consistently appears on “Pick” lists for irrigated and limited irrigation systems thanks to its stable performance.

TAM 115

A dual-purpose variety offering both grain yield and grazing potential, with enhanced disease and insect resistance.

- Strengths: Excellent milling and baking quality, large seed, high test weight, strong drought tolerance, and resilience against leaf, stripe, and stem rust, greenbug, and wheat curl mite (which contributes to Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus (WSMV) resistance).

- Adapted across High Plains, Rolling Plains, Blacklands, and even Western Kansas/Eastern Colorado. Performs well under irrigation and good dryland conditions—but less reliable under severe dryland stress due to lower tillering capacity.

TAM 205

TAM 205 is a newer dual-purpose variety known for its strong milling and baking quality paired with unmatched disease resistance. It is highly adaptable across systems and is a strong option for both grain and forage.

Strengths:

- Exceptional milling and baking quality

- Good forage potential

- Broad resistance (leaf, stripe, stem rust; WSMV; Fusarium head blight)

- High test weight and large seed

TAM 113

A reliable dryland performer with good grain and forage potential, especially under stress.

- Strengths: Solid grain yield, decent milling quality, and forage use. Early maturing with strong emergence and tillering – valuable in challenging environments. Offers resistance to stripe, leaf, and stem rusts.

- Remaining a steady Dryland “Pick” in High Plains trials thanks to its adaptability.

Reminder: Organic farmers need to make seed purchase arrangements early (well before planting season) to ensure they have an adequate supply of untreated seed.

Protein Content vs. Protein Functionality

Farmers often watch protein percent, but researchers emphasize that protein functionality—how protein behaves in dough—is more important. While there’s no easy field test for this, variety choice remains a strong predictor.

When evaluating economics, consider total protein yield (bushels × protein percent). Sometimes a lower-yielding but higher-protein field can be more profitable than a high-yield, low-protein one.

Of course, protein levels don’t appear out of thin air. They’re the result of fertility, management, and soil health—areas where organic systems work a little differently than conventional.

Nitrogen and Organic Systems

One point of clarification: organic wheat does not suffer from a “late-season nitrogen challenge” so much as it requires planning ahead for higher yields. Excellent varieties and management can unlock yield potential, but only if soil fertility is built to support them.

- Cover crops can provide up to 100 lbs of nitrogen per acre.

- Manure composts from chicken or dairy sources can supply around 40 lbs of nitrogen per 1,000 lbs applied.

- These are slow-release, biologically active forms of nitrogen. They need to be managed in advance so nutrients are available as the wheat grows.

- Liquid organic N sources exist, but they are generally too expensive to justify based on the modest yield increases in wheat.

This means success in organic wheat fertility comes from building the soil and feeding the crop over the long term, not chasing protein with late-season nitrogen shots. The key takeaway is that organic fertility is a long game—cover crops and compost must be planned well in advance to match the yield potential of high-quality varieties like TAM 114 and TAM 205.

TAM Varieties and Seed Saving

Beyond fertility, seed access and seed-saving rights also matter to organic growers when planning for the future. All TAM varieties are public releases and not under Plant Variety Protection. Farmers can legally save and replant TAM seed for their own use. This is especially valuable in organic systems where untreated seed availability can be limited.

Why This Matters

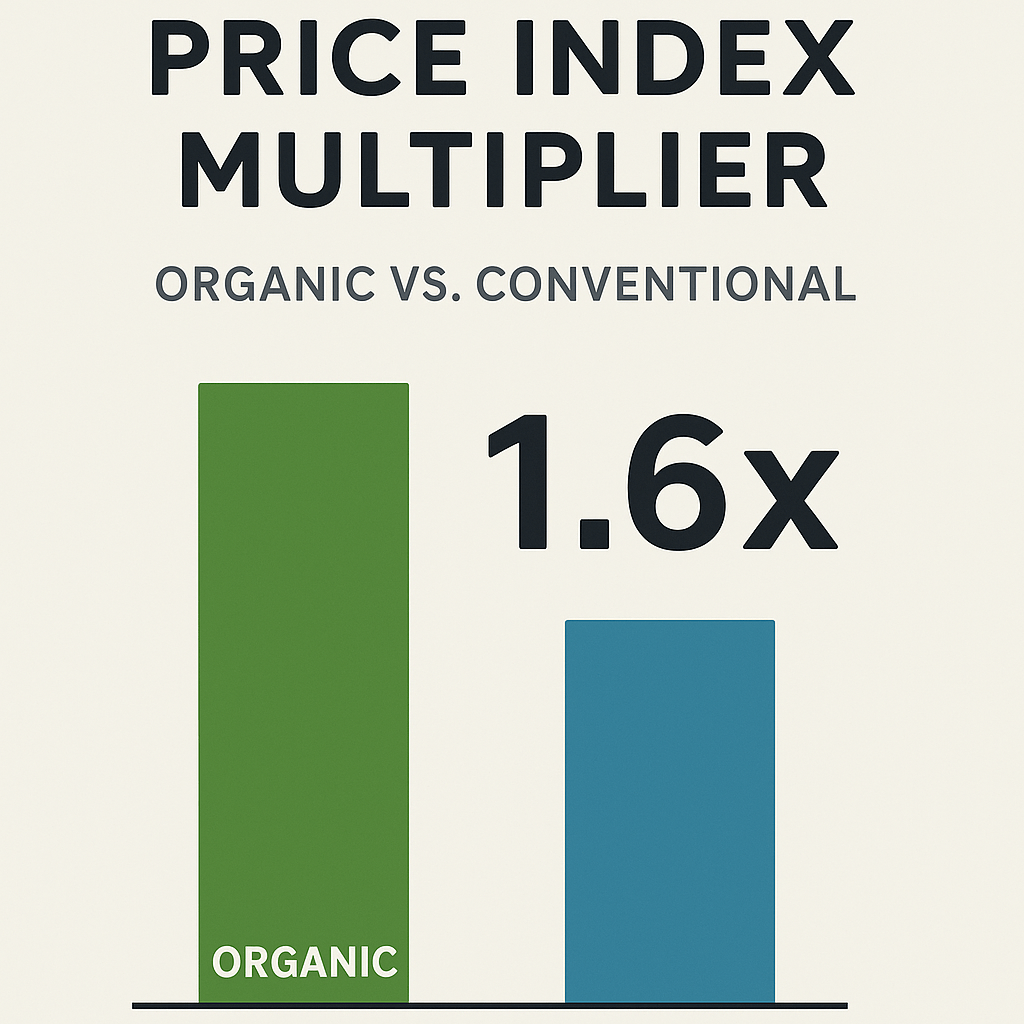

In conventional systems, buyers reward bushels. In organic systems, millers and bakers want quality along with yield. Understanding both milling and baking traits—and managing fertility to match variety potential—helps organic growers capture more value.

As we look ahead, TAM 114 remains a cornerstone for organic production, but TAM 205 is quickly emerging as a variety that combines yield, quality, and resilience. With the right fertility planning and variety choice, Texas organic wheat can continue to meet both market demand and farmer profitability.

By combining resilient TAM varieties with thoughtful organic fertility planning, Texas wheat growers can continue to deliver grain that is profitable on the farm and dependable in the marketplace.

Resources for Growers

- Texas A&M AgriLife Today – Wheat Picks highlight top-performing varieties by Texas A&M AgriLife

https://agrilifetoday.tamu.edu/2023/08/17/wheat-picks-highlight-top-performing-varieties-by-texas-am-agrilife/ - Texas A&M AgriLife Extension – Grain Variety Picks for Texas High Plains 2024–2025 (PDF)

https://lubbock.tamu.edu/files/2024/08/Grain-Variety-Picks-for-Texas-High-Plains-2024-2025.pdf - Texas A&M Department of Soil & Crop Sciences – Two new wheat varieties announced by Texas A&M AgriLife

https://soilcrop.tamu.edu/department-updates/two-new-wheat-varieties-announced-by-texas-am-agrilife/ - Texas A&M AgriLife Variety Testing – 2022–2023 Wheat Picks List, High Plains (PDF)

https://varietytesting.tamu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2022-2023-Wheat-Picks-List-High-Plains.pdf - Agseco Seeds – TAM 114 Variety Profile

https://www.agseco.com/tam114