A common critique I hear—often from people who genuinely support organic—is that large-scale organic farms and advanced technology somehow “lose the ideals” associated with organic agriculture. The image many people carry is a small farm with diverse plantings, hedgerows, wildlife habitat, and hands-on management. In contrast, when they see a large organic operation using sensors, software, GPS-guided equipment, and streamlined logistics, they sometimes conclude that it is no longer “true organic.”

I understand where that reaction comes from. But as an Extension Organic Specialist, I also find it deeply frustrating, because it reflects a misunderstanding of what organic agriculture is and what it must become if it is going to have real impact. If we want organic to remain a small niche system, then we can keep it mostly hand-scale. But if we want organic to become mainstream—meaning millions of acres managed under organic standards—then organic will necessarily look like agriculture: mechanized, planned, measured, and managed with modern tools.

Organic is a Production Standard, not a Farm Size

The most important clarification is this: organic is defined by a regulated production and handling standard, not by farm size or “farm aesthetics.” In the United States, organic is governed under the USDA National Organic Program (NOP), which sets requirements for:

- prohibited and allowed substances

- soil fertility and crop nutrient management

- pest, weed, and disease control approaches

- recordkeeping, traceability, and annual inspection

- avoidance of excluded methods (including genetic engineering)

A farm can be 20 acres or 20,000 acres and still follow the same legal standard. Scale does not automatically determine whether a farm is ecologically sound, ethically managed, or agronomically competent. I have seen small farms that are poorly managed and large farms that are exceptionally well managed. The reverse is also true. The difference is not the size—it is the management system and the accountability.

Why “Big Organic” Triggers Concern (and Why Some of It is Valid)

Concerns about large-scale organic often fall into a few categories:

- Minimum-compliance farming

Some fear that large operations will do the least required to meet certification rather than aiming for continuous improvement in soil function and ecological resilience. - Simplified landscapes

Large farms can have fewer field borders, fewer habitat features, and fewer “visible signs” of biodiversity. This is a real risk if the production system is not designed intentionally. - Monoculture and rotation weakness

Large farms can drift toward narrow crop sequences, especially when markets or processing infrastructure favor a few commodities. - Values and trust

Organic is a consumer trust program. When consumers associate “corporate” with “profit over stewardship,” they worry the label becomes marketing rather than meaning.

These concerns should not be dismissed. They are worth discussing. But the mistake is assuming that technology or scale automatically causes poor outcomes. Poor outcomes come from poor management decisions, weak incentives, or weak enforcement—not from tractors, sensors, or data.

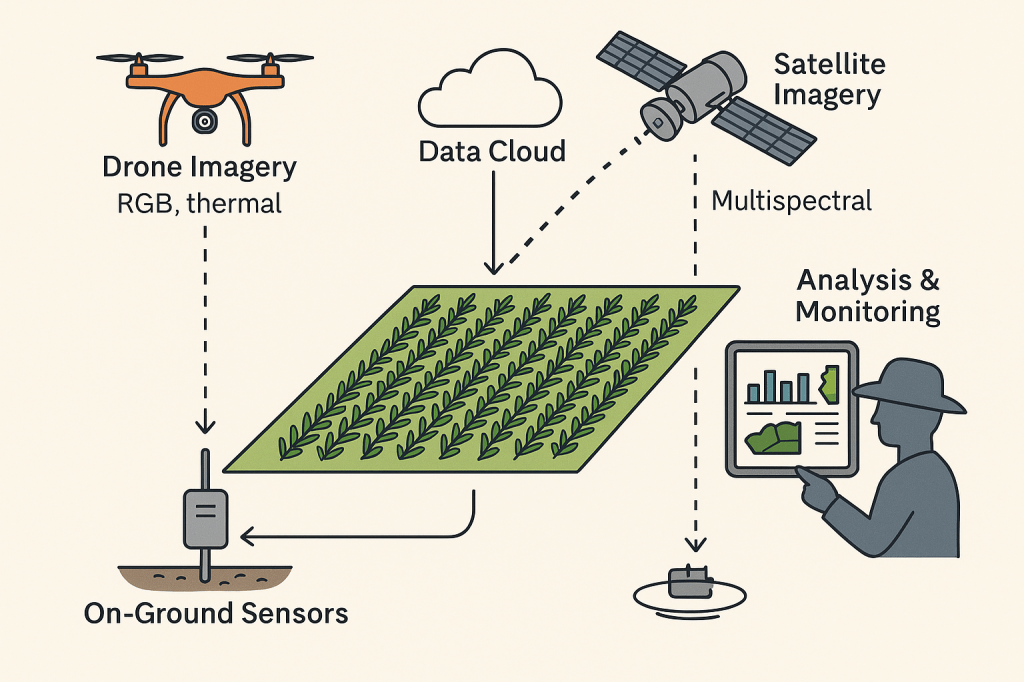

Technology is Not Anti-Organic: It Can Improve Stewardship

Organic farming is not defined by low technology. It is defined by the intentional avoidance of certain synthetic inputs and the use of systems-based management to support crop productivity and soil health. Technology can support that goal.

1) Sensors and irrigation efficiency

Water management is one of the clearest examples where technology aligns with organic principles. Soil moisture sensors and irrigation scheduling tools can:

- prevent over-irrigation

- reduce nutrient leaching and runoff risk

- improve root health and drought resilience

- reduce disease pressure associated with prolonged leaf wetness and saturated soils

In real-world farming, “using less water” is not a public relations statement—it is a measurable conservation outcome.

2) Nutrient management and nitrogen efficiency

Organic nitrogen (N) does not usually come from synthetic fertilizers. It comes from:

- composts and manures

- cover crops (especially legumes)

- mineralization of soil organic matter

- allowed inputs such as certain mined minerals and biological amendments

But organic nitrogen is also less predictable in timing and availability than synthetic N. Precision tools that improve the timing and placement of nutrients can reduce losses and improve crop response. Better nutrient planning is not “industrial.” It is good agronomy.

3) Weed and pest monitoring systems

Organic systems often rely on prevention, competition, timing, and mechanical control. Technology supports this by improving decision-making:

- mapping weed pressure zones

- documenting scouting results

- tracking crop stage and pest thresholds

- improving spray timing for allowed products that are highly timing-dependent

- strengthening records for compliance and traceability

Organic does not become less organic when it becomes more measured. In many cases, it becomes more defensible and more reliable.

The Scaling Reality: Organic Cannot Become Mainstream Without Looking Like Agriculture

Here is the contradiction I see repeatedly:

- People want organic to expand and become a major part of agriculture.

- But they also want organic to remain small, hand-scale, and “pre-modern.”

Those two goals cannot fully coexist.

If organic expands into a mainstream system, it will require:

- mechanization and labor efficiency

- stable supply chains and processing capacity

- agronomic decision support tools

- investment in equipment, storage, and logistics

- advanced recordkeeping and traceability systems

These are not signs that organic has failed. They are signs that organic is being implemented at a scale where it can influence land stewardship and food systems in meaningful ways.

A useful analogy is medicine: we may admire the “natural” remedies of the past, but if we want health outcomes at population scale, we use systems, research, logistics, and quality control. Organic agriculture, if it is to influence millions of acres, will also require systems and quality control.

The Real Question is Not “Small vs Large” — It’s “Well-Managed vs Poorly Managed”

When we focus on scale, we miss the more important scientific questions:

- Is soil organic matter improving over time?

- Is aggregate stability improving (meaning the soil holds together better under water impact)?

- Is infiltration increasing and runoff decreasing?

- Are nutrients cycling efficiently, or being lost through leaching and erosion?

- Is biodiversity supported through rotations, habitat, and reduced toxicity risk?

- Are weeds being managed through integrated strategies rather than emergency reactions?

- Are pests managed through ecological approaches and targeted interventions?

These are measurable outcomes. They are also where organic systems can succeed or fail, regardless of farm size.

A “Both/And” Vision for Organic

Organic agriculture needs both:

The ecological heart of organic

- soil building

- rotations

- biodiversity

- prevention-based pest management

- conservation practices that protect water and habitat

The infrastructure and tools to function at scale

- organic seed systems and breeding programs

- equipment and mechanical weed control innovation

- precision irrigation and nutrient planning

- traceability systems that protect market integrity

- research-based decision support tools

If we demand the heart without the infrastructure, organic stays fragile, expensive, and limited.

If we build infrastructure without the heart, organic becomes hollow and purely transactional.

The goal is not to keep organic small. The goal is to keep organic meaningful.

Closing Thought

I want organic to remain grounded in stewardship and biological systems. I also want organic to be agronomically credible, economically viable, and scalable enough to matter. That means I will continue supporting farmers—large and small—who are doing the hard work of growing crops under organic standards while improving soil function and resource efficiency.

Organic should not be judged by whether it “looks old-fashioned.”

Organic should be judged by whether it produces food and fiber with integrity, measurable conservation outcomes, and long-term resilience.

References (U.S. Organic Standards)

USDA National Organic Program Regulations (7 CFR Part 205)

https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-7/subtitle-B/chapter-I/subchapter-M/part-205

USDA AMS National Organic Program (program overview)

https://www.ams.usda.gov/about-ams/programs-offices/national-organic-program