Soil sampling is an essential practice in agriculture, providing a foundation for informed decision-making regarding soil management and crop production. The process involves collecting soil samples from multiple locations within a field to analyze for nutrient content, pH levels, organic matter, and other soil properties. This analysis offers a snapshot of the soil’s health and fertility, guiding farmers and agronomists in customizing fertilizer applications and other soil amendments to meet the specific needs of their crops. By tailoring these practices based on soil test results, producers can optimize plant growth, increase crop yields, and reduce the risk of over-application of fertilizers, thereby minimizing environmental impact.

The benefits of soil sampling extend beyond the immediate improvement of crop production. It plays a crucial role in sustainable agriculture by helping to maintain soil health over the long term. Healthy soil supports a diverse microbial ecosystem, improves water retention and drainage, and enhances the soil’s ability to store carbon, contributing to the mitigation of climate change. Moreover, by understanding the soil’s condition, farmers can adopt practices that prevent soil degradation, such as erosion and nutrient depletion, ensuring the land remains productive for future generations. Thus, regular soil sampling is a key tool in the pursuit of sustainable farming, enabling the efficient use of resources while protecting and enhancing the natural environment.

Click a Link Below to Scroll Down

- Click a Link Below to Scroll Down

- Taking a Soil Test

- What does a soil test tell you about soil?

- Soil Tests Typically Taken

- Haney Soil Health Test

- Soil Wet Aggregate Stability Test

- Using the PLFA Soil Health Test

- Trace Genomics Testing

- Soil Labs: this is not a complete list by any means but simply a guide.

- Other Resources:

Taking a Soil Test

Taking a proper soil test involves a series of steps to ensure the accuracy of the soil sample, which in turn, provides reliable data for making informed agricultural decisions. Here is a detailed list of how to conduct a proper soil test:

- Planning the Sampling Strategy: Determine the appropriate time and pattern for sampling. Ideally, soil should be sampled at the same time each year, avoiding periods immediately after fertilizer application. Divide the field into uniform areas based on soil type, topography, previous crop history, and apparent soil variability.

- Gathering the Right Tools: Equip yourself with a clean, rust-free soil probe, auger, and/or shovel, and a plastic bucket. Avoid using metal containers which can contaminate the soil sample with trace metals.

- Sampling Depth: Collect soil samples at a consistent depth. For annual crops, a depth of 6-8 inches is typical, whereas for perennials, samples may be taken from a deeper profile, depending on the root zone of the crop.

- Collecting the Soil Sample: In each area, collect soil from at least 15-20 random spots to avoid bias. Mix these sub-samples in the plastic bucket to form a composite sample. This approach ensures the sample represents the overall area rather than specific spots.

- Labeling and Documentation: Clearly label each sample with a unique identifier, noting the sampling date, location, depth, and any other relevant information. This step is crucial for keeping records and interpreting the results accurately.

- Preparing the Sample for Analysis: Allow the soil to air-dry at room temperature; avoid heating or sun-drying as this can alter the soil chemistry. Once dry, remove stones, roots, and other debris, and break up clumps. A quart-sized sample is typically sufficient for laboratory analysis.

- Choosing a Laboratory: Select a reputable soil testing laboratory that uses methods appropriate for your region’s soils. Provide the laboratory with detailed information about your crop, previous fertilizer applications, and any specific concerns you have.

- Interpreting the Results: Once you receive the soil test report, review the recommendations on fertilization and soil amendment. If necessary, consult with an agronomist or extension specialist to understand the implications for your specific situation and crops.

- Implementing Recommendations: Use the soil test results to adjust your fertilization strategy, applying nutrients according to the crop’s needs and the soil’s current status. This targeted approach helps avoid overuse of fertilizers, promoting environmental sustainability and economic efficiency.

- Monitoring and Adjusting: Soil testing should be a regular part of your farm management practice. Re-test soils in each field every 2-3 years or more frequently if significant amendments have been made, to monitor changes in soil health and fertility over time.

Above is a standard soil probe that will last you for years – well worth the cost. Next is a picture of WD-40 which is a great spray for the probe to keep the soil from sticking in the probe. Clay soils can be difficult to get “out” but WD-40 eliminates the issue.

Following these steps ensures that the soil testing process is thorough, and the results are reliable, forming a solid basis for sustainable soil management and crop production strategies.

What does a soil test tell you about soil?

Soil testing encompasses a range of analyses that evaluate different aspects of soil health, soil properties, and soil fertility, providing critical information for agricultural management and environmental assessment. Here are several key types of soil tests commonly conducted:

- pH Test: Measures the acidity or alkalinity of the soil on a scale from 1 to 14. Soil pH affects nutrient availability to plants and microbial activity in the soil. A pH of 7 is neutral, values below 7 are acidic, and values above 7 are alkaline.

- Nutrient Content Test: Assesses the levels of essential nutrients, including nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) (often referred to as NPK), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sulfur (S), and micronutrients like iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), boron (B), molybdenum (Mo), and chlorine (Cl). This test helps in determining fertilizer needs.

- Organic Matter Test: Evaluates the amount of organic matter in the soil, which influences water retention, nutrient availability, and soil structure. High organic matter content is beneficial for soil health and plant growth.

- Soil Texture Test: Determines the proportions of sand, silt, and clay in the soil. Texture affects water retention, drainage, and nutrient availability, and it guides management practices such as irrigation and cultivation.

- Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) Test: Measures the soil’s ability to hold and exchange cations (positively charged ions) such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium. CEC is influenced by soil texture and organic matter content and affects soil fertility.

- Electrical Conductivity (EC) Test: Assesses the soil’s electrical conductivity, which is an indicator of salinity levels. High salinity can affect plant growth by inhibiting water uptake.

- Lime Requirement Test (Buffer pH Test): Determines the amount of lime needed to adjust the soil pH to a desirable level for crop production. This is crucial for acidic soils needing pH correction.

- Soil Water Holding Capacity: Measures the amount of water the soil can hold and make available to plants. This is important for irrigation planning and drought management.

- Soil Aggregate Stability: measure how well aggregates hold together during a disturbance event. These tests can predict soil risks or management needs and track changes to soil overtime. The SLAKES APP is a great tool that is easy to use on your smartphone.

- Heavy Metal Test: Identifies the presence and concentration of heavy metals such as lead (Pb), arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), and mercury (Hg), which can be toxic to plants and humans at high levels.

- Soil Health Tests: These are comprehensive tests that may include biological indicators such as microbial biomass, enzyme activities, and earthworm counts, assessing the overall health and biodiversity of the soil.

Soil Tests Typically Taken

Of course, a normal soil test or what you might call a Regular Soil Test discussed above is a must. These are not usually expensive, +/- $15 or more with micronutrients. This test is mostly meaningless unless I have previous year’s results to see what is going on. I have taken literally thousands of soil samples and often I will see something show up that is off the charts. I am not known to panic when I see a problem because I am not going to react to that test unless I know it has steadily been a problem that is just getting worse. For instance, we can see pH swings in sand from one year to the next. Before I lime a soil, I may take a second sample just to verify I need lime. $15 soil test is cheaper than $60 per acre lime application.

Second, I like to have a Haney Soil Test done to get an idea of the availability of many nutrients in an organic system and to better understand the overall “healthiness” of the soil. It is not cheap compared to the typical soil test. Most labs charge $50 so you don’t usually just send everything in for a Haney Test. Again, the results are only good if you have several years’ worth of data to see if you are getting better.

Next, is the Soil Wet Aggregate Stability Test. This test used to assess the ability of soil aggregates to resist disintegration when exposed to water.

Last, is the PLFA Test or Phospholipid Fatty Acid Test. This test measures the biomass of the microbes in the soil and is one of the tests that is currently being conducted to determine the microbial population of soil. See down below for more.

This is an example of soil test costs from one lab. They are all about the same price from multiple labs.

Haney Soil Health Test

The Haney Soil Health Test is a comprehensive analysis designed to evaluate the overall health and fertility of the soil through a holistic approach. Developed by Dr. Rick Haney, a research soil scientist with the USDA, this test goes beyond conventional chemical nutrient analysis by incorporating measurements of soil organic matter, microbial activity, and the potential for nitrogen and phosphorus mineralization. The test employs a unique set of assays, including the Solvita CO2-Burst test, which measures the amount of carbon dioxide released from the soil after rewetting dry soil to assess microbial respiration and activity. This is an indicator of the soil’s biological health and its ability to cycle nutrients.

Additionally, the Haney Test evaluates the water extractable organic carbon (WEOC) and water extractable organic nitrogen (WEON), which are believed to more accurately reflect the pool of nutrients that are readily available to plants than traditional extraction methods. By assessing both the chemical and biological fertility of the soil, the Haney Test provides a more integrated view of soil health, guiding farmers in optimizing their management practices to support sustainable agriculture. The results from the Haney Test can help in making more informed decisions on the application of fertilizers and amendments, aiming to enhance soil health, reduce environmental impact, and improve crop yields by fostering a more vibrant and resilient soil ecosystem. This test is particularly valuable for those engaged in regenerative agriculture and organic farming, as it aligns with the principles of nurturing soil life and function to achieve productive and sustainable farming systems.

The Haney Soil Health Test provides a comprehensive set of results that offer insights into both the chemical and biological aspects of soil health. The test results typically include several key indicators:

- Soil Health Score: A composite index that reflects the overall health of the soil, integrating various test components to give a summary assessment. This score helps in comparing the health of different soils or the same soil over time.

- Water Extractable Organic Carbon (WEOC): Measures the amount of organic carbon that is easily available in soil water, indicating the potential food source for microbes.

- Water Extractable Organic Nitrogen (WEON): Indicates the level of organic nitrogen available in soil water, which can be readily used by plants and soil organisms.

- CO2-C Burst (Carbon Mineralization): Assesses microbial respiration by measuring the burst of carbon dioxide released from the soil after it is moistened, indicating active microbial biomass and soil organic matter decomposition rate. This number will be between a low of <10 and a very high score is >200. This will be in parts per million or mg/kg which is the same.

- Soil pH: The acidity or alkalinity of the soil, which affects nutrient availability and microbial activity.

- Electrical Conductivity (EC): A measure of the soil’s electrical conductivity, which can indicate salinity levels that might affect plant growth.

- Extractable Phosphorus, Potassium, Magnesium, Calcium, and other nutrients: Provides information on the levels of these essential nutrients that are available for plant uptake, based on water extractable methods.

- Nitrate-Nitrogen and Ammonium-Nitrogen: Measures the inorganic forms of nitrogen available in the soil, which are directly usable by plants.

- Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC): Indicates the soil’s ability to hold and exchange cations (positively charged ions) important for plant nutrition.

- Organic Matter %: The percentage of soil composed of decomposed plant and animal residues, indicating the potential of soil to retain moisture and nutrients.

- Recommendations for Fertilizer and Lime Applications: Based on the test results, specific recommendations are made to address nutrient deficiencies or pH imbalances, tailored to the crop being grown and the goals of the farmer.

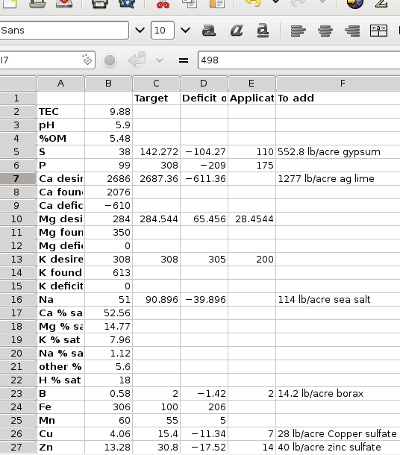

These results (see below for a sample) offer a detailed picture of the soil’s current condition, highlighting areas where improvements can be made to enhance soil health, fertility, and productivity. By focusing on both the biological and chemical facets of soil health, the Haney Test guides farmers towards more sustainable and efficient management practices, emphasizing the importance of soil life in agricultural ecosystems.

Soil Wet Aggregate Stability Test

Soil wet aggregate stability testing is a method used to assess the ability of soil aggregates to resist disintegration when exposed to water. This test is crucial for understanding soil structure, which plays a vital role in the soil’s ability to support plant growth. In this method, soil aggregates are placed on a sieve and submerged in water, where they are subjected to gentle agitation to simulate natural conditions such as rainfall. The stability of these aggregates is then measured by determining how much of the soil remains intact after exposure to water. The results provide valuable insights into the soil’s resistance to erosion, its ability to retain water, and its overall structural integrity.

The importance of wet aggregate stability testing lies in its direct relationship to soil health and crop productivity. Stable aggregates improve water infiltration and retention, reducing the risk of surface runoff and erosion, which can lead to nutrient loss and reduced soil fertility. Additionally, well-structured soils with high aggregate stability allow roots to penetrate more easily, access nutrients, and withstand environmental stresses such as drought. For growers, maintaining high aggregate stability is essential for sustaining healthy crops and promoting long-term soil fertility, making this test a critical component of comprehensive soil health assessments.

The four methods you can use for measuring soil aggregate stability include: Slaking image analysis, Cornell Rainfall Simulator, Wet Sieve Procedure, Mean Weight Diameter

Slaking Image Analysis:

- Overview: This method uses a smartphone app, like SLAKES, to capture and analyze images of soil aggregates submerged in water. The app tracks the degree to which the aggregates break apart (slake) over time. (easy to download to your smartphone and I can even use it!)

- Why It’s Used: It offers a quick, accessible way to assess aggregate stability in the field without the need for specialized lab equipment. For farmers, this method is very easy and practical to use, making it ideal for routine soil health monitoring, though it may lack the precision needed for scientific research.

- Click here to see a great explanation of this app and how to use on your farm.

Cornell Rainfall Simulator:

- Overview: Soil aggregates are placed under a simulated rainfall, and the test measures how well the soil resists breaking apart and eroding. The simulator mimics natural rainfall to assess the soil’s response.

- Why It’s Used: This method is particularly useful for understanding soil erosion potential and how soil structure withstands actual rainfall events. For farmers, it provides insights into how well their soil can handle heavy rains, though it typically requires access to specialized equipment only available at a few labs.

Wet Sieve Procedure:

- Overview: In this method, soil aggregates are placed on a series of sieves and submerged in water. The sieves are then mechanically agitated to simulate natural conditions like water flow. The amount of soil that remains on the sieves is measured to determine stability.

- Why It’s Used: It is a widely recognized and precise laboratory method for quantifying the stability of soil aggregates under wet conditions. Farmers might find this method less accessible due to its complexity, but it provides highly reliable data that can inform long-term soil management decisions. Typically used by researchers.

Mean Weight Diameter (MWD):

- Overview: This method calculates the average size of soil aggregates that remain stable after being subjected to wet sieving. It provides a single value that reflects the overall stability of the soil.

- Why It’s Used: MWD is a commonly used metric in soil science because it offers a straightforward way to compare the stability of different soils and management practices. For farmers, this method can be useful for tracking the impact of different practices on soil structure over time, though it’s usually conducted in a lab setting.

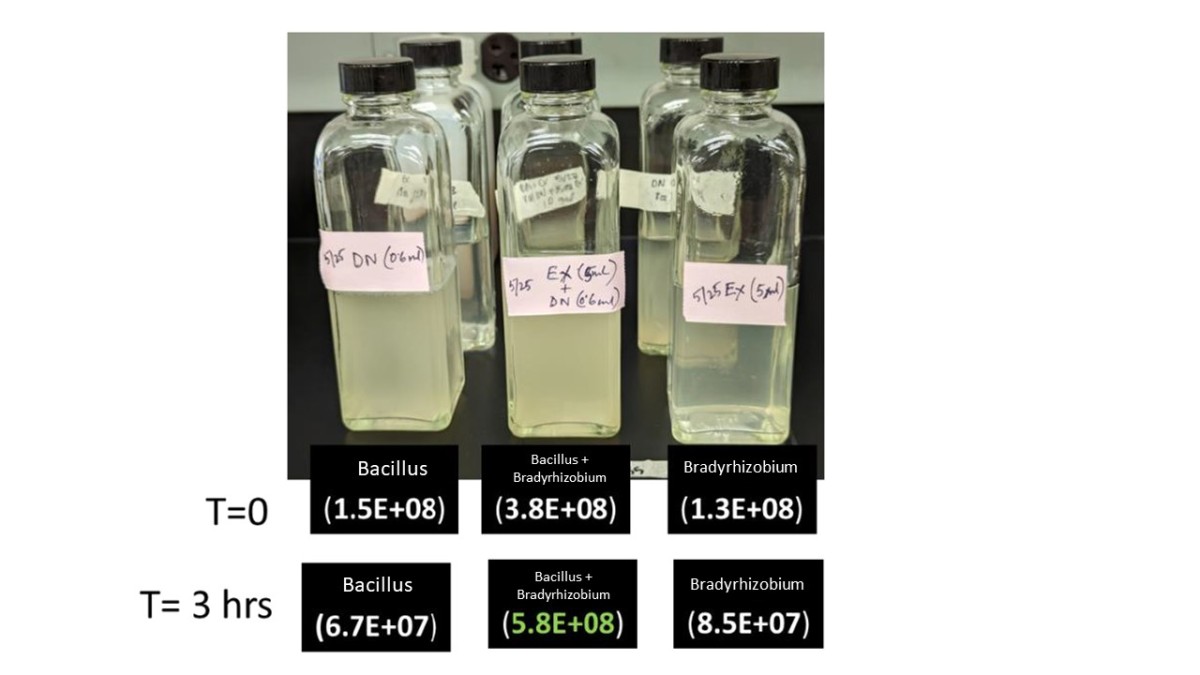

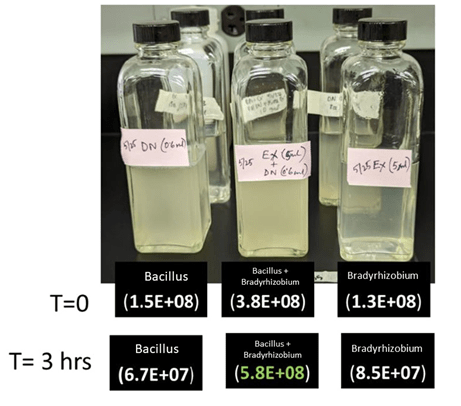

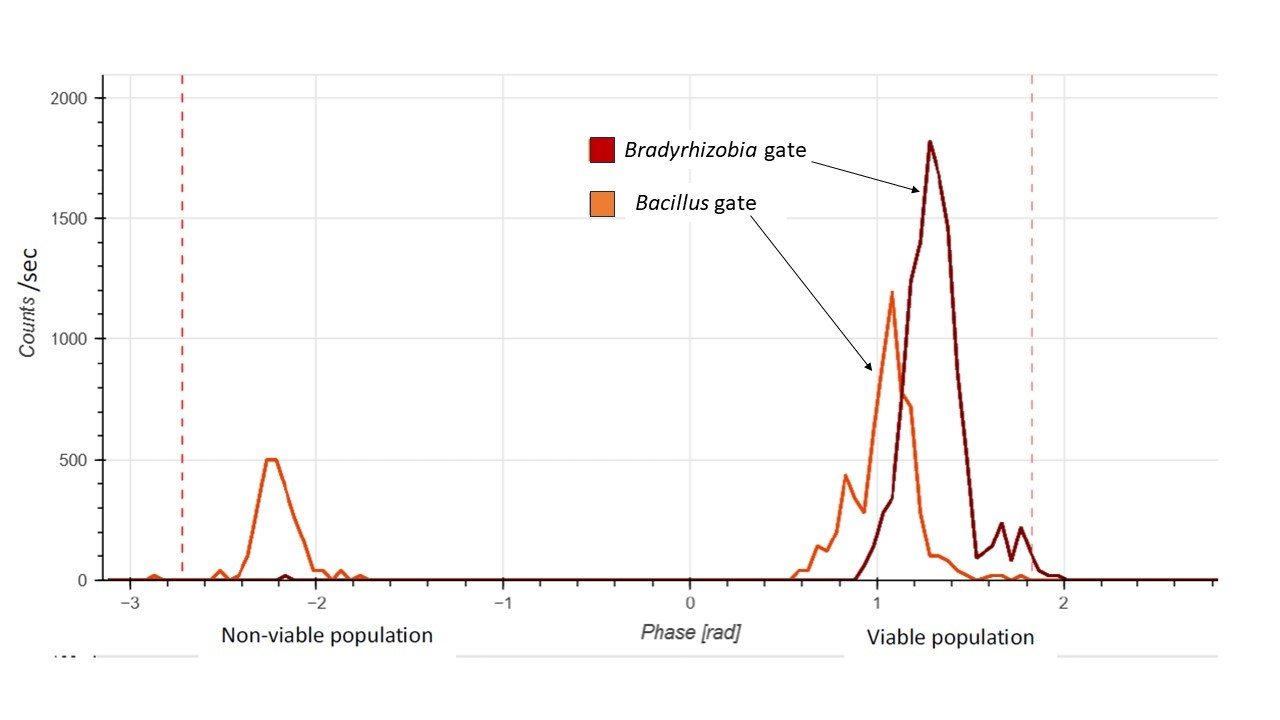

Using the PLFA Soil Health Test

The Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) analysis is a powerful tool for assessing soil health, focusing on the microbial community within the soil. Phospholipid fatty acids are components of cell membranes in all living organisms, and their presence and composition in soil samples can provide detailed information about the microbial community structure, including bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes, and other soil organisms.

How the PLFA Test Works

The PLFA test involves extracting phospholipids from a soil sample and then analyzing the fatty acid components. Each group of microorganisms has a unique fatty acid profile, allowing scientists to identify and quantify the types of microbes present in the soil. This information can be used to assess biodiversity, microbial biomass, and the balance of fungal to bacterial communities, which are critical indicators of soil health and ecosystem function.

Importance of PLFA Analysis for Soil Health

- Microbial Biomass: The total amount of microbial biomass is a direct indicator of soil organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling capabilities. High microbial biomass often correlates with healthy, fertile soil.

- Community Composition: The composition of the microbial community can indicate the soil’s condition and its ability to support plant growth. For example, a higher fungal to bacterial ratio is often found in soils with good structure and organic matter content.

- Soil Stress and Disturbance: Changes in microbial community composition can also indicate soil stress, contamination, or the impact of agricultural practices such as tillage, crop rotation, and the use of fertilizers or pesticides.

- Baseline and Monitoring: Establishing a baseline microbial community profile allows for the monitoring of changes over time, assessing the impact of management practices on soil health.

Applications of PLFA Analysis

- Agricultural Management: Helping farmers and agronomists understand the impact of farming practices on soil microbial communities and, by extension, soil health and crop productivity.

- Environmental Assessment: Evaluating the restoration of soil ecosystems following contamination or disturbance.

- Research: Advancing our understanding of soil microbial ecology and its relationship to plant health, climate change, and ecosystem services.

Advantages and Limitations

The PLFA test offers a direct, rapid assessment of living microbial biomass and community structure, providing valuable insights into soil health that are not captured by chemical soil tests alone. However, it requires specialized equipment and expertise to perform and interpret, and the cost may be higher than traditional soil tests. Despite these limitations, the PLFA analysis remains a critical tool for comprehensive soil health assessment, guiding sustainable soil management and conservation efforts.

Great publication you can read on understanding these Soil Health Tests. Just click the link below:

How to Understand and Interpret Soil Health Tests

The “take home” message is not soil testing only, but records of soil tests you can see over time!

Trace Genomics Testing

Thanks to Dr. Justin Tuggle for sending this information to me about Trace Genomics. This is a fairly new company that basically tells you what kinds of microbes you have in the soil, good or bad, to then help make decisions of what you need to do. It may be a new variety, a biostimulant or a soil treatment. I would like to see some producers try this new test and share some examples of what it can do. Click here to see their webpage.

A quote from Trace Genomics

“We engage in hi-definition DNA sequencing down to the functional gene level. This lets us mine the soil microbiome to identify specific functions, commonly referred to as “indicators,” which can provide actionable insights to help you maximize soil health. One example is a phosphorus solubilization indicator, which analyzes the quantified capability of microbes in the soil to release bound phosphate and make it plant available.”

“In just one soil test you get insights covering more than 70 crops and more than 225+ pathogens. TraceCOMPLETE pairs unmatched soil analysis with hi-definition genomic sequencing to deliver an unrivaled collection of pathogen and nutrient insights. It can drive agronomic action in your most critical decision areas to help you make meaningful management decisions.“

Soil Labs: this is not a complete list by any means but simply a guide.

- Texas A&M Soil and Water Testing

- https://soiltesting.tamu.edu/

- 2610 F&B Road

- College Station, TX 77845

- 979-321-5960

- Ward Laboratories, Inc.

- www.wardlab.com

- 4007 Cherry Ave, Kearney, NE 68847

- (800) 887-7645

- Regen Ag Lab

- www.regenaglab.com

- 31740 Highway 10, Pleasanton, NE 68866

- (308) 627-0065

- TPS Lab

- www.tpslab.com

- Joe Pedroza, Business Development Manager

- 4915 W. Monte Cristo Rd, Edinburg, TX 78541

- Office: (956) 383-0739

- Cell: (956) 867-7480

- Waypoint Analytical

- waypointanalytical.com

- 2790 Whitten Rd, Memphis, TN 38133

- (901) 213-2400

- Midwest Laboratories

- https://midwestlabs.com/

- 13611 B Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68144

- contactus@midwestlabs.com

- Office: (402) 334-7770

- Fax: (402) 334-9121

Other Resources:

- Farming with Soil Life

- Building Soils for Better Health

- A Minimum Suite of Soil Health Indicators for North American Agriculture

- Managing Soil Biology for Organic Farming

- Soil Balancing Basics for Organic Farming

- The Economics of Transitioning to Certified Organic Farming