When it comes to hay production, many farmers assume that bales harvested from the same field will contain similar nutrient levels. The differences across fields was evident in a recent article by Michael Reuter in Progressive Forage1. His article and data show us all, the significant differences even among bales from the same field. Understanding and managing these differences can make a big impact, especially for organic farmers who want to optimize livestock nutrition and maintain a consistent quality of forage.

Variability in Nutrient Composition: What the Data Tells Us

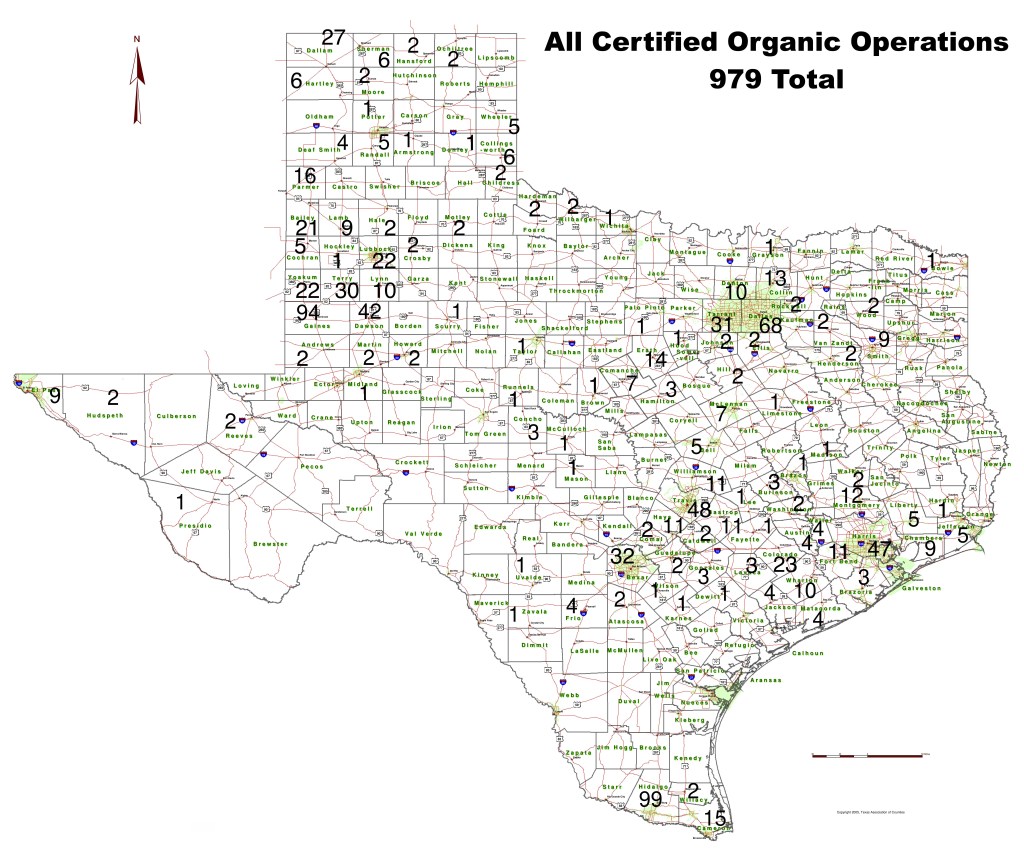

The following table from the article1 presents the nutrient composition and analysis of 20 individual bales randomly sampled from an 86-acre hay field, which was managed as a unit and harvested all at the same time:

The analysis of the 20 hay bales showed surprising variability in key nutrients such as Crude Protein (%CP), fiber content (measured as %ADF and %NDF), and essential minerals like Calcium (%CA) and Phosphorus (%P). Summary statistics of the nutrient composition are presented below:

Crude protein, for example, varied from 9.7% to 15.9%. This 6.2 percentage point difference could significantly influence the nutritional value of hay fed to livestock.

Fiber levels also differed substantially. The ranges in Acid Detergent Fiber (%ADF) and Neutral Detergent Fiber (%NDF) directly affect how digestible the hay is and how much livestock will eat. Calcium and phosphorus levels, which are critical for bone health and metabolic functions, also showed noteworthy differences between bales.

Why Does This Variability Happen?

Even in a well-managed hayfield, several factors can contribute to this nutrient variability:

- Soil Fertility Differences: Organic amendments like compost or manure may not be evenly spread across the field. Variability in soil nutrients can cause different areas of the field to produce hay with varying nutrient levels.

- Crop Rotation and Plant Diversity: Rotating different crops or allowing natural diversity in the field is beneficial for soil health, but it can also lead to differences in how well each crop absorbs nutrients.

- Pest, Weed, and Microclimate Effects: Organic fields often have more variability in pest pressure, weed growth, and microclimates. These differences can lead to uneven growth, which in turn affects nutrient content.

Managing Nutrient Variability

To minimize these differences and provide more consistent forage quality, farmers can take several practical steps:

- Soil Testing: Regularly test soil across different sections of the field. This helps identify nutrient deficiencies or hotspots, allowing targeted amendment application.

- Even Amendment Application: When applying compost, manure, or other organic fertilizers, try to ensure even distribution across the field. Variability in amendment application is a key factor in nutrient inconsistency.

- Use Cover Crops: Cover cropping can help improve soil structure and increase nutrient cycling, which leads to more uniform plant growth.

- Monitor Harvest Stages: Harvesting at a consistent plant maturity stage across the field can help reduce variability. Plants harvested at different growth stages can differ significantly in nutrient content.

- Matching Regular Soil and Forage Testing: Applying soil nutrients based on soil tests and then testing multiple hay bales gives a clearer picture of the overall nutrient profile from start to finish. Testing hay allows adjustments in livestock feeding to meet nutritional needs effectively and maybe even save money!

Why Managing Nutrient Variability Matters

In organic systems, where synthetic supplements are not allowed, maximizing the natural nutrient content of forages is essential. Variable hay quality can significantly impact livestock health, as inconsistencies in nutrition may lead to reduced growth rates, lower milk production, or other health issues. Moreover, optimizing the quality of on-farm forage can reduce the need for expensive purchased supplements and any organic supplements are not cheap.

Maintaining consistent forage quality also supports animal welfare, which is a core value of organic and sustainable farming. Healthy, well-fed animals are more resistant to disease, aligning with the organic principle of promoting natural immunity and reducing intervention.

Conclusion

Variability is a natural part of farming, but with informed management, we can turn that variability into an opportunity for learning and improvement—ultimately providing better feed for our livestock and keeping our farms resilient.

1.Data Source: October 1, 2024 issue of Progressive Forage written by Michael Reuter, Analytical Services Technical Manager at Dairy One Cooperative Inc. and Equi-Analytical Labs.