I get lots of general questions about what to use for fertilizer in organic agriculture. It is generally accepted that compost is good for organic, but does it have to be certified organic compost? What about manure? Can you buy some of these processed fertilizer products? What are the rules for fertilizers?

Click on any link below to scroll down!

- 205.203 Soil fertility and crop nutrient management practice standard.

- What about some of these organic fertilizers you can buy?

- Some newer organic fertilizers – protein hydrolysates

- Where do you buy this stuff in bulk?

- Other Resources:

205.203 Soil fertility and crop nutrient management practice standard.

The first place to start is with the National Organic Program rules and regulations.

(a) The producer must select and implement tillage and cultivation practices that maintain or improve the physical, chemical, and biological condition of soil and minimize soil erosion.

(b) The producer must manage crop nutrients and soil fertility through rotations, cover crops, and the application of plant and animal materials.

(c) The producer must manage plant and animal materials to maintain or improve soil organic matter content in a manner that does not contribute to contamination of crops, soil, or water by plant nutrients, pathogenic organisms, heavy metals, or residues of prohibited substances. Animal and plant materials include:

First let’s talk about raw animal manure, which must be composted unless it is:

(a) Applied to land used for a crop not intended for human consumption or,

(b) Incorporated into the soil not less than 120 days prior to the harvest of a product whose edible portion has direct contact with the soil surface or soil particles or

(c) Incorporated into the soil not less than 90 days prior to the harvest of a product whose edible portion does not have direct contact with the soil surface or soil particles.

Second on the list is composted plant and animal materials produced through a process. This process involves the mixing of manures generally with some carbon sources like leaves, bark, hay, hulls, etc. to create a product that is:

(a) Establish an initial Carbon: Nitrogen ratio of between 25:1 and 40:1 and

(b) Maintains a temperature of between 131 °F and 170 °F for 3 days using an in-vessel or static aerated pile system or

(c) Maintains a temperature of between 131 °F and 170 °F for 15 days using a windrow composting system, during which period, the materials must be turned a minimum of five times.

Last in this list of NOP materials are Uncomposted plant materials. This is typically what you might call mulches like bark chips, leaves, grass, etc. These are used a lot in perennial crop systems to control weeds and add fertility over time.

As you can see all of these products are from a natural source and that natural source does not have to be a certified organic source. Neither the animals or the plants that you use to make compost or just get raw manure or mulch has to be from an organic farm.

What about some of these organic fertilizers you can buy?

Let’s go back to the rules: A producer may manage crop nutrients and soil fertility to maintain or improve soil organic matter content in a manner that does not contribute to contamination of crops, soil, or water by plant nutrients, pathogenic organisms, heavy metals, or residues of prohibited substances by applying, if you follow these restrictions below.

(a) A crop nutrient or soil amendment included on the National List of synthetic substances allowed for use in organic crop production (click here for that list).

(b) A mined substance of low solubility.

(c) A mined substance of high solubility: Provided the substance is used in compliance with the conditions established on the National List of nonsynthetic materials prohibited for crop production.

(d) Ash obtained from the burning of a plant or animal material, except as prohibited in the list below.

(e) A plant or animal material that has been chemically altered by a manufacturing process: Provided, that the material is included on the National List of synthetic substances allowed for use in organic crop production.

The producer (that is you or any company that makes an organic fertilizer) must not use:

(a) Any fertilizer or composted plant and animal material that contains a synthetic substance not included on the National List of synthetic substances allowed for use in organic crop production.

(b) Sewage sludge (biosolids from a city sewage plant or from a septic tank or a mix of either source with plant material to make a compost).

(c) Burning as a means of disposal for crop residues produced on the operation: Except, That, burning may be used to suppress the spread of disease or to stimulate seed germination. We sometimes do a heat process to “sterilize” a plant material before using. Doubt you will ever need this part!

Some newer organic fertilizers – protein hydrolysates

Protein hydrolysates are increasingly recognized for their role in organic fertilization strategies, offering a sustainable approach to enhance plant growth and soil health. Derived from proteins through hydrolysis, which breaks down proteins into smaller chains of amino acids or even individual amino acids, these products provide a readily available source of nitrogen and other nutrients to plants. This process can involve enzymatic, chemical, or thermal hydrolysis methods, each with its specific advantages and applications.

Nutrient Availability: Protein hydrolysates are particularly valued in organic agriculture for their rapid assimilation by plants. Unlike synthetic fertilizers, these organic nutrients are in forms that plants can easily absorb and utilize, leading to efficient nutrient use and potentially reducing the need for additional fertilization.

Soil Health: Beyond providing nutrients, protein hydrolysates contribute to soil health. They support the growth and activity of beneficial microorganisms, which play a crucial role in soil nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and the suppression of soil-borne diseases. This can lead to improved soil structure, water retention, and fertility over time.

Real Life Example: Consider a scenario where an organic farmer is growing lettuce, a crop that demands a consistent supply of nitrogen for leaf development. By applying a protein hydrolysate-based fertilizer, the farmer can provide a quick-acting source of nitrogen that is readily available for uptake by the lettuce plants. This not only supports the rapid growth of the lettuce but also contributes to the overall soil health by feeding the microbial life within the soil.

Problems? Yes, there are problems with some of these products. Nutrient availability is an issue. We have done experiments, and the product(s) may be slow to work in the plant or the actual nutrients may be lower than stated. This can be caused by a number of factors such as binding to soil or volatilization, but it does mean you need to know your source and product.

Sources: There are just too many to list! This new source for organic fertilizer is great to see but there are a lot of companies getting into this market. Just know that they are not cheap, companies can be far away meaning shipping is a big cost, and you need to know the product well. Please, please be sure that the product you are considering is OMRI approved. Sometimes these blends are with synthetic sources…….

Where do you buy this stuff in bulk?

South Plains Compost

- PO BOX 190, Slaton, Texas 79364

- Toll-free: 888-282-2000

- Office: 806-745-1833

- FAX: 806-745-1170

- Physical Address: 5407 East Highway 84Slaton, Texas 79364

Sigma AgriScience

- Office: 281-941-6944

- info@sigma-agri.com

- Corporate Office

580 Maxim Dr., Boling, TX 77420 - Boling Plant

- 2565 FM 1096, Boling, TX 77420

- Winnsboro Plant

- 400 All Star Rd, Winnsboro, TX 75494

Morgan Bulk

- 3075 FM 1116, Gonzales, Tx. 78629

- Phone: 830-437-2855

- Kerry Mobile: 830-857-3919

- Bobby Morgan Mobile: 830-857-4761

- Fax: 830-437-2856

7H Nutrients (Pelleted Product)

- 8063 S US HWY 183, Gonzales, TX

- Briant Hand

- Mobile: 830-857-4340

- 7hhand@gmail.com

Green Cow Compost

- Location: 1557 CR 339 Dublin, TX 76446

- P.O. BOX 449 Dublin, TX 76446

- Office: 254-445-2011

- greencowcompost@yahoo.com

Microbes Biosciences (Rhizogen Granular)

- 1544 Sawdust Rd #505, The Woodlands, TX 77380

- Office: 281-367-7500

- info@microbesbiosciences.com

Viatrac Fertilizer

- Office: 361-293-DIRT (3478)

- Freight/Plant: 936-590-4522

- Email: mbarnett@viatracfertilizer.com

- 500 Airport Road, Yoakum, TX 77995

- Brett Banner (sales)

- Mobile: 936-552-1426

- bbanner@viatracfertilizer.com

Nature Safe Fertilizers

- 5601 N Macarthur Blvd, Irving, TX, 75038

- Main Phone: (469) 957-2725

- Main Fax: (469) 957-2655

- Natalie Starich (sales)

- Mobile: (559) 410-3097

- natalie.starich@naturesafe.com

Organics by Gosh

- 2040 FM 969, Elgin, TX 78621

- Commercial: 512-872-1434

- Residential: 512-276-1211

- Alexis Beckley

- alexis@organicsbygosh.com

- Organicsbygosh.com

Earthwise Organics

- 13081 State Highway 172, La Ward, Texas 77970

- Office: (956) 207-0500

- office@earthwiseagriculture.net

Ferticell

- Corporate: (480) 361-1300

- Sales: (480) 398-8511

- Fax: (480) 500-5967

- info@ferticellusa.com

- 5865 S. Kyrene Rd., Suite 1, Tempe, AZ 85283

True Organic Products

- 1909 Fairhaven Gateway

- Georgetown, TX 78626

- Mobile (737) 403-0064

- Corporate (831) 375-4796

- Barret Milam-Regional Sales Representative-Texas

- bmilam@true.ag

- true.ag

Other Resources:

- Building Soils for Better Crops

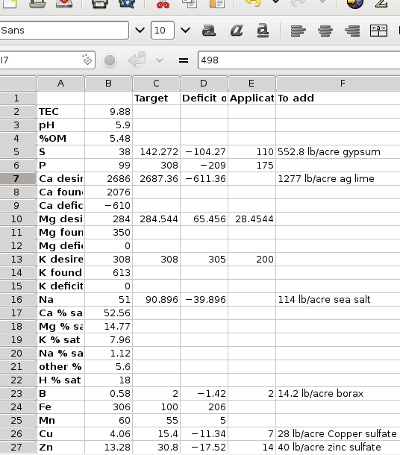

- Soil Balancing Basics for Organic Farming

- Biostimulants – The Next New Frontier for Ag

- Best Cover Crops for Weed Control and Fertility

- What is the True Cost of Compost (or Manure) in 2024

- Composts and Herbicides Don’t Mix

- Managing Soil Biology for Organic Farming

- The Economics of Transitioning to Certified Organic Farming

- Farming with Soil Life

- Managing Soil Biology for Organic Farming

- Soil Balancing Basics for Organic Farming

- The Economics of Transitioning to Certified Organic Farming