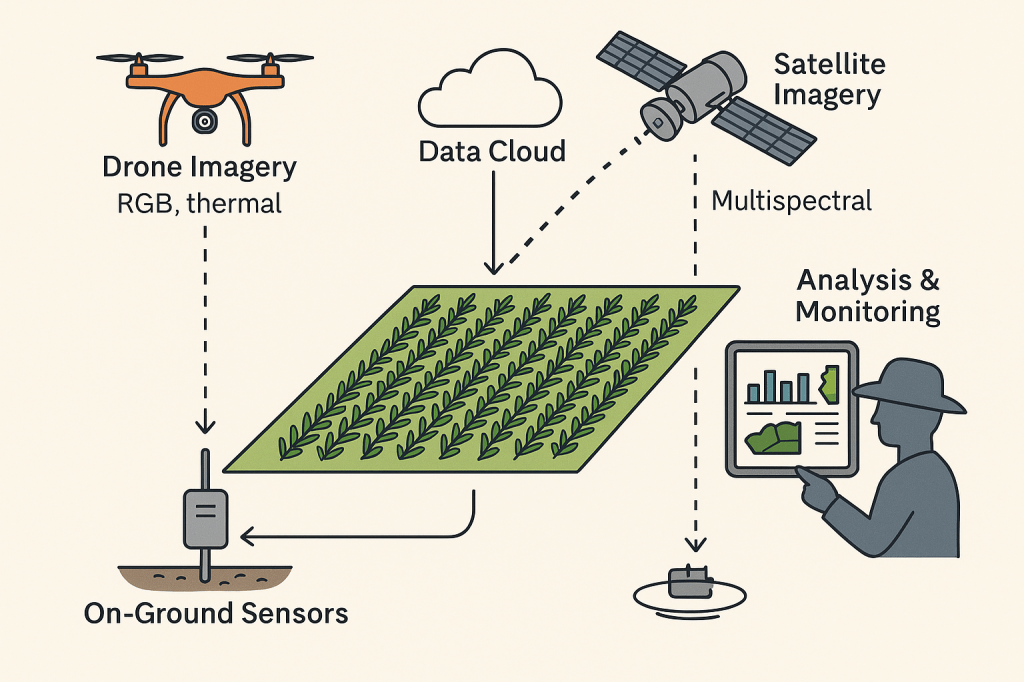

Smart sensing is transforming how we understand plant health in organic systems. By integrating satellite and drone imagery, in-field sensors, and artificial intelligence, we can now detect stress in crops long before symptoms appear. This technology doesn’t replace the farmer’s eye—it strengthens it, helping us protect soil biology, use resources more wisely, and make better management decisions.

Learning from Students and Staying Curious

This past Saturday (October 18), a group of high school students invited me to speak about their project on smart plant monitoring. They were designing a device to track plant health in real time. Their questions—about soil, light, and water—were sharp and curious. It reminded me why I love this field: whether we’re students or seasoned farmers, we’re all learning how to listen to plants a little better.

Their project also made me reflect on how far we’ve come. When I started in Extension, plant monitoring meant walking fields, taking notes, and maybe digging a soil sample. Now, we’re using satellites orbiting hundreds of miles above the earth and sensors no bigger than a pencil eraser to understand how crops respond to their environment.

From Satellites to Soil: The New Eyes of Agriculture

In organic production, timing is everything. A crop under stress can lose days of growth before we even notice it. But RGB drone and satellite imaging now allow us to spot stress early by detecting subtle changes in leaf color, canopy density, or reflectance.

Even more advanced are multispectral and hyperspectral sensors, which measure how plants reflect light across visible and infrared wavelengths. These patterns can reveal water stress, nitrogen deficiency, or disease pressure—well before a plant wilts or yellows.1

Thermal cameras add another layer. Drought-stressed plants reduce transpiration, causing leaf temperature to rise—a change that infrared sensors can detect long before visible damage occurs.2

Once the imagery is captured, we still rely on ground-truthing—walking to the coordinates, checking the crop, soil, and often pulling tissue samples. This blend of technology and touch keeps data meaningful.

Predictive Systems: Seeing Stress Before It Starts

The most exciting progress in recent years has been predictive capability. AI-powered analytics now integrate drone imagery, IoT soil data, and weather patterns to learn what “normal” looks like for a crop. When the system detects deviations—like a drop in chlorophyll fluorescence or a rise in leaf temperature—it flags them early.3

One powerful method is solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF), which measures photosynthetic efficiency. Subtle declines in fluorescence intensity can indicate stress from drought, salinity, or nutrient imbalance days before the plant shows visible symptoms.4

Meanwhile, IoT sensor networks are spreading across fields. These small devices monitor soil moisture, pH, canopy temperature, and even sap flow, sending real-time data to cloud dashboards that can automatically adjust irrigation schedules.5

This isn’t just smart—it’s proactive agriculture.

Image acquisition setups using different sensors (i) DJI Matrice 600 Pro with a Sony Alpha 7R II, 42.4-megapixel RGB camera mounted on it(Sapkota, 2021), (ii) A close-range laboratory imaging system with a Micro-Hyperspec VNIR sensor in controlled lighting condition (Dao et al., 2021a), (iii) HyperCam on the tripod, Fluke TiR1, Lci leaf porometer, Infragold as well as dry and wet references targets (Gerhards et al., 2016) (iv) Chamber equipped with two Raspberry Pi 3B + and an ArduCam Noir Camera with a motorized IR-CUT filter and two infrared LEDs (Sakeef et al., 2023).6

Why This Matters for Organic Systems

Organic farming depends on living systems—soil microbes, organic matter, and ecological balance. Unlike conventional systems, we can’t rely on quick chemical fixes. We need to detect stress early enough to respond biologically—through irrigation management, microbial inoculants, or balanced foliar nutrition.

Smart sensing tools help us manage that complexity. When we combine spectral imagery, soil data, and climate information, we begin to see the farm as an interconnected ecosystem rather than a collection of separate fields.

Monitoring also supports stewardship. Water-quality sensors can now detect salinity and bicarbonate buildup that harm roots over time. Linking those readings with AI-derived stress maps helps producers align soil chemistry, water quality, and plant physiology in one continuous feedback system.7

The Human Element Still Matters

Even with all this technology, the farmer’s experience is irreplaceable. Data can tell us something changed, but it takes experience to know why. Was that NDVI dip caused by poor drainage, pests, or a timing issue in irrigation?

Technology should not distance us from the field—it should bring better insight to our decisions. As I often tell growers, just as computers need rebooting, we occasionally need to “reboot” our interpretation—to align the data with what we know from hands-on experience.

A Partnership Between Grower, Plant, and Sensor

When those students asked how technology fits into farming, I told them this: smart monitoring doesn’t make agriculture less human—it makes it more informed.

The future of organic production is a partnership between the grower, the plant, and the sensor. When all three communicate clearly, we grow more than crops—we grow understanding. And in that understanding lies the future of any sustainable agriculture.

Further Reading

- Farmonaut. Hyperspectral Imaging in Agriculture Market 2025 Advances. https://farmonaut.com

- Botany with Parul. Artificial Intelligence in Plant Stress Analysis: A Game Changer for Agriculture. https://botanywithparul.com

References

- Dutta, D. et al. (2025). “Hyperspectral Imaging in Agriculture: A Review of Advances and Applications.” Precision Agriculture, 26(3): 445–463. ↩︎

- Cendrero-Mateo, M.P. et al. (2025). “Thermal and Spectral Signatures of Plant Stress.” Frontiers in Plant Science, 16:31928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1631928 ↩︎

- Chlingaryan, A. et al. (2025). “Machine Learning for Predictive Stress Detection in Crops.” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 218:107546. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168169924011256 ↩︎

- Guanter, L. et al. (2024). “Solar-Induced Fluorescence for Assessing Vegetation Photosynthesis.” NASA Earthdata Training Series. https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/learn/trainings/solar-induced-fluorescence-sif-observations-assessing-vegetation-changes-related ↩︎

- Ahmad, L. & Nabi, F. (2024). Agriculture 5.0: Integrating AI, IoT, and Machine Learning in Precision Farming. CRC Press. ↩︎

- Chlingaryan, A. et al. (2025). “Machine Learning for Predictive Stress Detection in Crops.” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 218:107546. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168169924011256 ↩︎

- Gómez-Candón, D. et al. (2025). “Integrating Water Quality Sensors and Remote Sensing for Sustainable Irrigation.” Agricultural Water Management, 298:108072. ↩︎