Here are few things you might find interesting or helpful as you think about organic cotton planting in a few months (weeks). I will update this as I get new information, but it will be “here” to help anytime you need it.

If there is anything I need to add or change, please let me know. I want to keep this as up to date as possible. Click link in this Table of Contents below to scroll down.

- Cotton Varieties for Organic

- Cottonseed Quality – It Matters!

- Cotton Contacts:

- Cotton Buyers for Organic

- ORGANIC RESOURCES: Just click the link to see!

Cotton Varieties for Organic

Commercial Varieties Developed without Genetic Engineering Methods. Be sure that any seed treatments applied are OMRI approved and okayed by your certifier.

Upland Varieties

- Americot – UA48 (talked to Dr. Robert Lemon with NexGen and they hope to have some commercial varieties good for organic in a few growing seasons.)

- Brownfield Seed & Delinting – Varieties: BSD 224, BSD 4X, BSD 598, BSD 9X, Ton Buster Magnum. Currently, one new Tamcot variety is being reviewed for future commercialization and BSD has 2 new varieties being reviewed for future commercialization.

- Seed Source Genetics – CT 210, UA222, UA103, UA 107, UA114

- ExCeed Genetics – 6447 or 4344 (May Seed from Turkey where they do not grow GE cotton.)

- International Seed Technology (IST) – BRS 286, BRS 293, BRS 335, BRS 2353. Varieties from Brazil and certified in Texas.

Pima or Pima hybrids

- Gowan – 1432

Cottonseed Quality – It Matters!

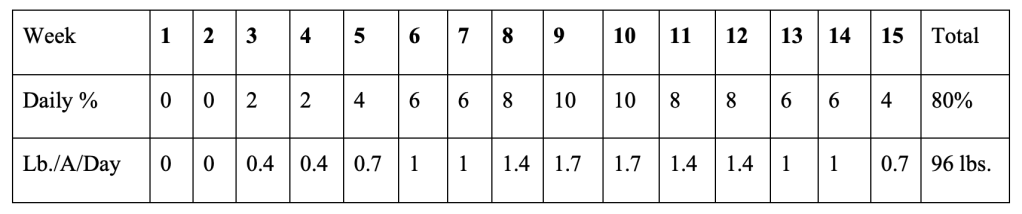

Cottonseed is sold in 50lb. bags as you all know but the number of seed in a bag can be drastically different depending on the variety. Typically, we see 220,000 – 230,000 seed or about 4,500 seed per pound but over the years we have seen cottonseed size go down such that we can have varieties approaching 6,000 seed per pound.

Seed germination for cotton is determined using two methods. A warm seed germination test would be to put the seed through 16 hours of 68 degrees then 8 hours of 86 degrees and do this for 4 days. Calculate the % germination which is the germinated seed number divided by the number of seed tested. 80 germinated seed/100 beginning seed tested * 100 = 80%

A cool seed germination test is simply keeping the seed at a constant 64.5 degrees for 24 hours for 7 days. Calculate the % germination.

If you want to read more about cotton seed testing this is a very recent article that is very helpful. Cotton Seed Quality Program Update

Cotton Contacts:

ExCeed Genetics (May Seed)

- Campbell, Terry

- Mobile: (806) 778-1208

- Email: terrycampbell1208@gmail.com

- Dosher, Jamie

- Mobile: (817) 304-3737

- Email: jamie@green-dirt.com

Brownfield Seed and Delinting

- Watson, Branden

- Bus: (806) 637-6282

- Mobile: (405) 332-6769

- Email: branden.watson.bsandd@gmail.com

- Forbes, Klint

- Bus: (806) 637-6282

- Mobile: (806) 548-1048

- Email: bsd.seed@aol.com

Gowan

- Neuenschwander, Rick

- Mobile: (806) 200-2851

- Email: neuenschwanderrick@gmail.com

Seed Source Genetics

- Jungmann, Edward

- Office: (361) 584-3540

- Cell: (361) 548-7560

- Email: eejungmann@gmail.com

International Seed Technology (IST)

- Fernandez, Francisco

- Cell: (305) 890-5468

- Email: fcofernandezg@ist-interseedtech.com

- Poveda, Martin

- Cell: (901) 831-0664

- Email: martin.poveda@ist-interseedtech.com

Cotton Buyers for Organic

No organic producer should ever begin planning for a crop without first organizing with a buyer to buy the crop. Cotton is not a crop to grow without a buyer since even storage can be difficult unless arranged in advance.

Texas Organic Cotton Marketing Cooperative

- Lehnen, Clay

- Bus: (806) 748-8336

- Email: clay@texasorganic.com

King Mesa Cotton Gin

- Harris, Hunter

- Bus: (806) 462-7351

- Email: king.mesa.gin.2@telmarkcotton.com

Woolam Gin

- Harris, Randi

- Bus: (806) 428-3314

- Mobile: (806) 759-9105

- Email: randi@woolamgintx.com

Jess Smith & Sons Cotton

- Burris, Joshua

- Bus: (661) 325-7231

- Mobile: (806) 407-6889

- Email: joshua@jesssmith.com

5 LOC

- Crossland, Brent

- Mobile: (919) 900-0057

- Email: brentcrossland@5loccotton.com

Allenberg Cotton Company

- Louis Dreyfus Company Subsidiary

- (901) 383-5000

TruCott Commodities

- Jarral Neeper, President

- (901) 383-5000

ORGANIC RESOURCES: Just click the link to see!

- Dr. Carol Kelly’s Webinar Update on Varieties

- Cover Crops in South Plains Cotton – Not possible, or is it?

- 2023 Cotton Performance Trials in the High Plains

- Cotton Seed Quality – Dr. Ben McKnight, Extension Cotton Specialist

- NC State Cotton Seed Quality Pictures (good to print out)

- Organic Cotton Variety Slides from Dr. Jane Dever (excellent)

- What is the True Cost of Compost

- Best Cover Crops for Weed Control and Fertility

- Organic Weed Control

- A list of approved organic products to use for pests of organic crops like cotton?

- Join Us in Enhancing Organic Cotton Production

- NOP Ruling on Organic Cottonseed

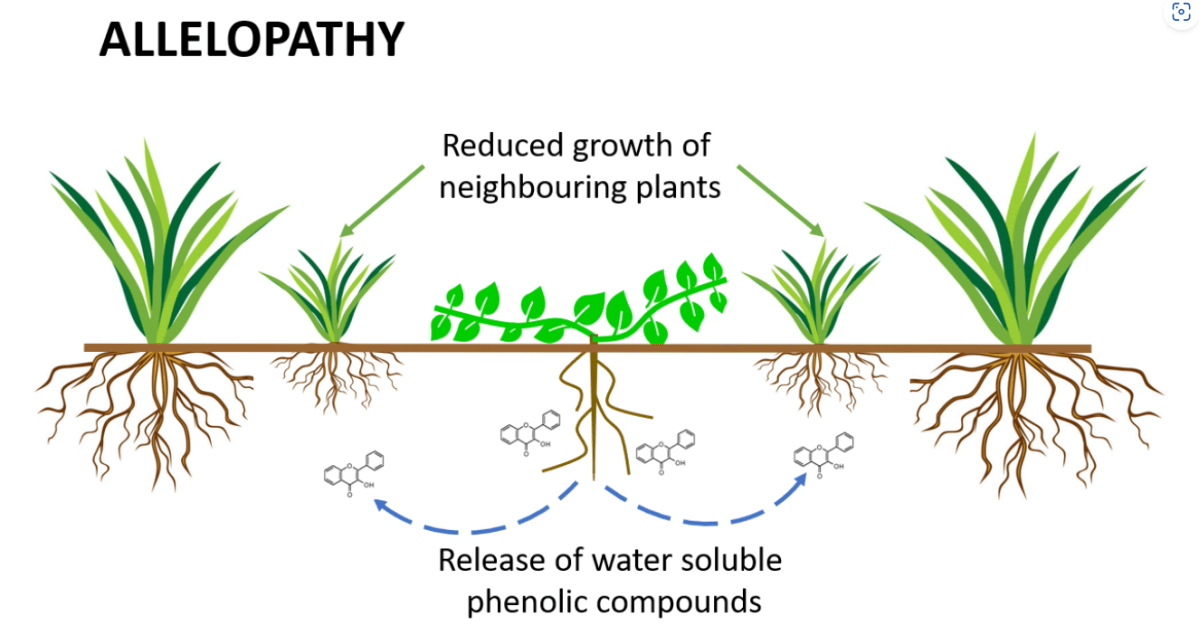

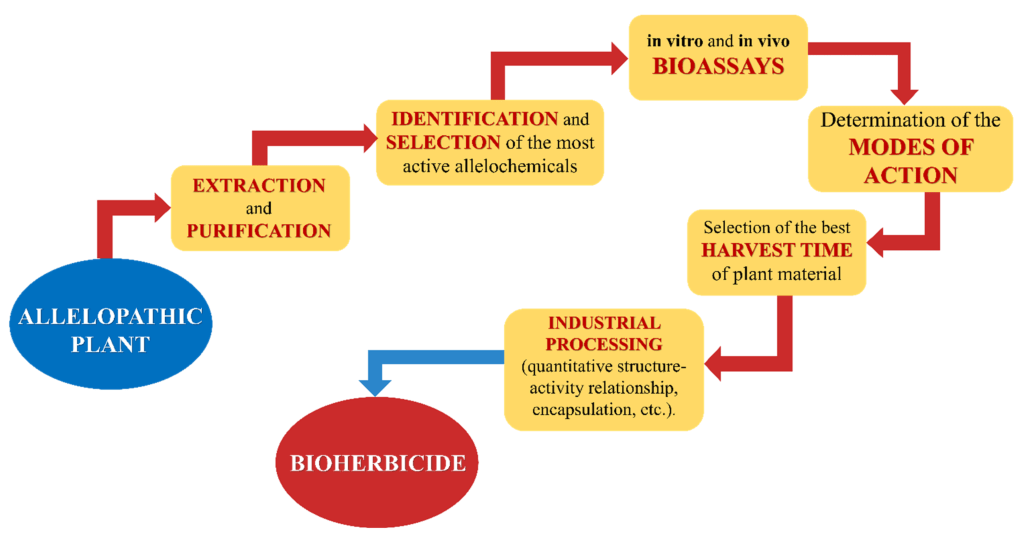

- Allelopathy – What is it, what has it, and how do we use it?

- Organic Seed May Soon Be Required

- Cotton Varieties for Organic Blog