In Extension, we’re often asked to help farmers and food businesses plan for the future—whether it’s transitioning acreage to organic, developing budgets, or evaluating the economics of new practices. One of the most common challenges we face is this: how do you plan for prices in an unpredictable market?

While no one can forecast future prices with certainty, that doesn’t mean we’re flying blind. We base our planning on something measurable, reliable, and rooted in history—and in organic agriculture, one of the most useful tools for this is a broad price index or multiplier.

Why Use a Price Multiplier?

Organic markets—like all markets—fluctuate. Prices are affected by everything from weather and input costs to consumer demand and global trade. But when we look at long-term trends, we begin to see patterns that can inform sound decision-making.

When we have access to strong market data—such as for organic corn, cotton, dairy, and many fruits and vegetables—we can use that data to create benchmarks. These help answer practical questions:

- What kind of price can I reasonably expect if I go organic?

- How much more can I budget for input costs and still break even?

- Will this transition pencil out?

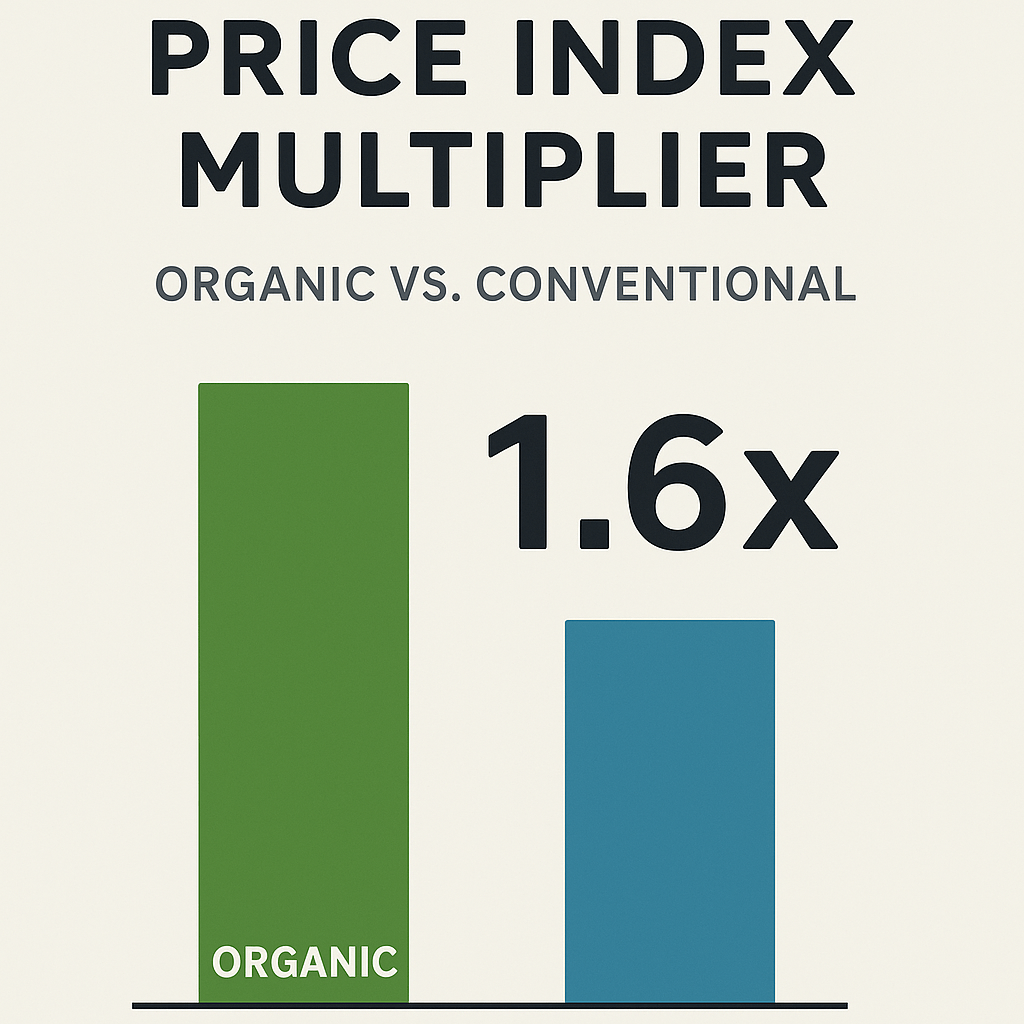

To answer these questions, we need a reference point—and that’s where a 1.6 multiplier comes in.

What Is the 1.6 Organic Multiplier?

The 1.6 multiplier means that organic farmgate prices tend to average about 1.6 times higher than conventional prices for many major commodities over the long run. That’s a 60% premium, based on real market data and USDA price tracking over the past decade or more. I happened to stumble onto this idea when I read an article in Progressive Dairy about conventional milk price forecasts through 2025. (Click to Read) This article made me wonder if I could use historical organic dairy milk prices in relation to conventional dairy milk prices and use this ratio to predict future organic prices. It was amazing to see what I kind of knew, that organic prices do follow with conventional prices for the most part!

So, this is not a guess. It’s backed by:

- USDA AMS organic market summaries for corn (1.6 is pretty stable for corn) and cotton (less stable as prices have been higher making the index 1.6-2.0 or higher).

- National organic dairy price reports, which show organic milk regularly selling at 1.5 to 1.65 times the price of conventional.

- Industry-wide organic vegetable and fruit pricing that shows farmgate premiums in the 1.5 to 1.7 range across categories like tomatoes, lettuce, and apples.

Whether you’re planning production, analyzing risk, or applying for a grant or loan, this index provides a realistic baseline. It is not too optimistic or too pessimistic and is useful for planning purposes.

When This Index Works—and When It Doesn’t

The 1.6 multiplier is a planning tool, not a crystal ball. It works best:

- When building enterprise budgets for row crops, dairy, and produce.

- When discussing profitability potential with transitioning farmers.

- When negotiating contracts or thinking through insurance or risk tools.

- In extension workshops, to help audiences grasp market potential quickly.

However, this index doesn’t capture every situation. Local sales, direct markets, specialty crops, and extreme weather or supply chain issues can cause premiums to fall below or rise above the average. Sometimes, organic produce in a saturated market may only bring in a 10–20% premium, while other times a rare variety or short supply can push that number above 2x (or higher) the conventional price.

Why It’s Still Useful

Despite those swings, planning requires a number—and the 1.6 index is a solid, evidence-based starting point.

When I help producers set up organic systems, I don’t want to promise the moon. Instead, it is better to offer realistic projections grounded in long-term national trends.

Always I encourage producers to:

- Adjust their projections up or down depending on crop, region, and market access.

- Keep checking updated USDA-AMS, Argus Media, or buyer data each year.

- Use the 1.6x benchmark as a baseline, not a guarantee.

Final Thoughts

As organic agriculture continues to grow, tools like this price index become more and more valuable. They help all of us in organic talk apples to apples with producers, gins, co-ops, lenders, and buyers. They also help demystify what can sometimes feel like a complex or volatile market.

My plan and my job is to keep helping farmers make decisions that are smart, sustainable, and rooted in good data.