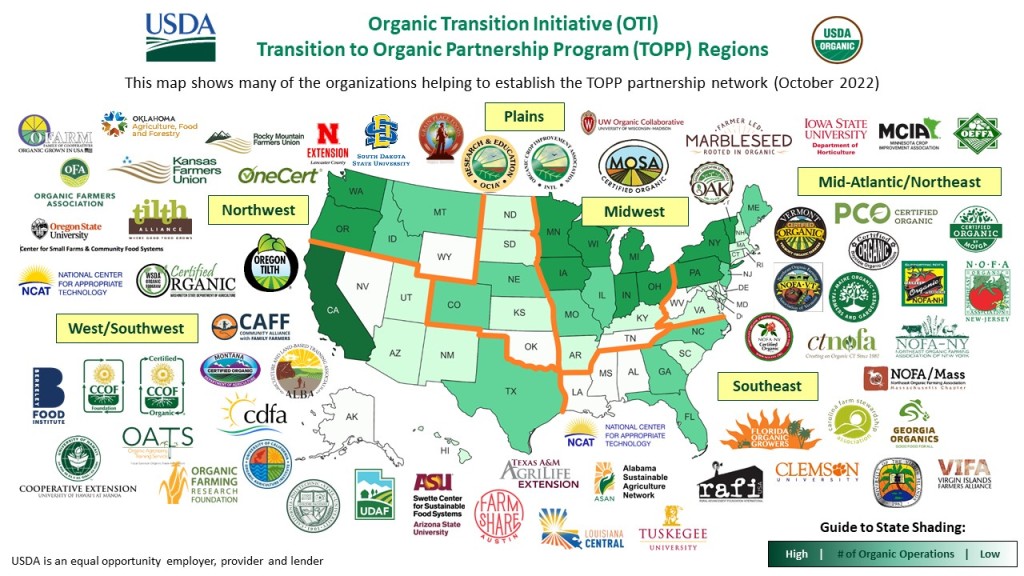

Texas TOPP is a five-year partnership program designed to effectively recruit, train, mentor and continually advise farmers who want to transition to organic production. Its overall goals are to build up successful Organic Farmer to Farmer Mentorships that are a part of a larger Organic Community Building program. Within this community will be developed organic resources available to both transition and certified growers, mentors, allied industry, and agencies that provide the needed help and support to a growing Texas organic movement. This Technical Assistance and Training will benefit both certified organic and transition organic while strengthening the overall organic program. Outside of this effort and yet integral to long term success is a Workforce Training and Development effort that focuses on how best to train future organic industry professionals.

Texas TOPP as a partnership program will be led by Texas A&M AgriLife Extension and the overall AgriLife Organic Program but with special partnerships that include Texas’ higher education institutions, USDA agencies, nonprofit organizations, and farm associations. Efforts of all participants will interact and impact conventional farmers, transitional organic and certified organic farmers and the many allied industry supporters of organic in Texas.

Texas TOPP will emphasize and solidify a commitment to organic agriculture by Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension and help ensure the future of organic within Texas agriculture for generations to come. More information will be coming but Texas Topp has already begun!