Beneficial insects, also known as biological control agents, play a crucial role in managing pest populations in organic crops, especially organic row crops. These insects help reduce the need for chemical pesticides, promote biodiversity, and support sustainable farming practices. Here’s a guide on how to integrate beneficial insects into your organic farming system, specifically for crops like cotton, peanut, corn, sorghum, rice, and wheat.

Table of Contents (click to find)

- Starting with Beneficial Insects

- Where to Buy Beneficial Insects

- Field Preparations

- Beneficial Insect Delivery and Distribution Methods

- Keeping Beneficial Insects in the Field

- Crop Varieties and Beneficial Insects

- Other Resources

Starting with Beneficial Insects

Incorporating beneficial insects into your pest management strategy is a smart, sustainable choice. These natural predators offer a highly effective alternative to organic insecticides, providing ongoing pest control without the need for frequent reapplications. The beneficial insect industry is growing, offering a wider variety of predators and parasitoids than ever before, making it easier to find the right ones for your specific pest issues.

Using beneficial insects helps maintain a balanced ecosystem, as they target pests without harming other beneficial organisms. This promotes biodiversity and long-term soil health, crucial for sustainable farming. Additionally, while the initial investment might be higher, the reduction in pesticide use can lead to significant cost savings over time.

Furthermore, employing beneficial insects supports compliance with organic standards, as it reduces reliance on even approved organic insecticides. This approach aligns with the principles of organic farming, enhancing natural processes and contributing to a healthier environment.

Lastly, it is not unusual to see this type of “pest control” continue to be self-sustaining as the introduced predators continue to live in your established habitat. Living on your farm year-round means that they are ready to go to work when you do! Take a look at this list below and know that these are the insect predators that are commonly available and listed on most websites. But if you find a problem or have a suggestion don’t hesitate to reach out.

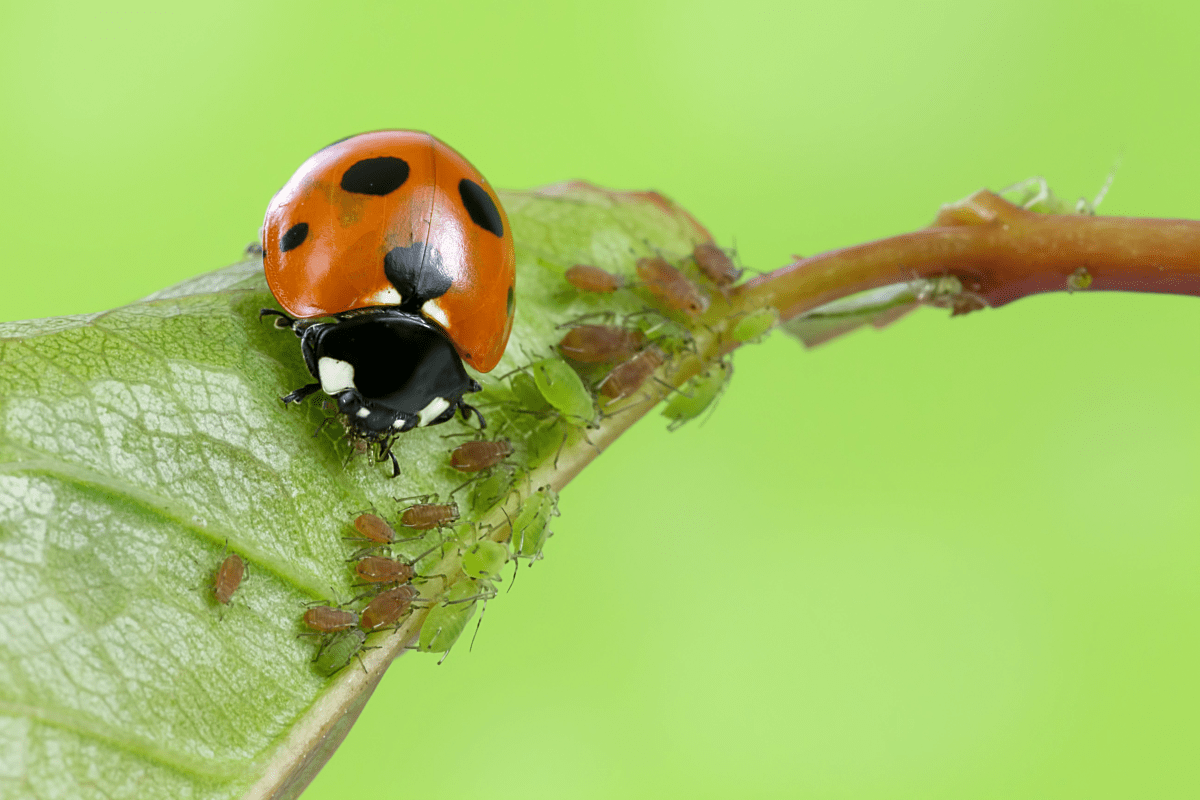

Predatory Beetles

Lady Beetle (Joseph Berger, Bugwood.org)

- Hippodamia convergens (Convergent Lady Beetle) Targets: Aphids, scale insects, mealybugs, spider mites.

- Coccinella septempunctata (Seven-Spotted Lady Beetle) Targets: Aphids, small caterpillars, scale insects, mealybugs.

- Harmonia axyridis (Asian Lady Beetle) Targets: Aphids, scale insects, mites, thrips.

- Carabidae (Ground Beetles) Targets: Slugs, snails, caterpillars, root maggots, other soil-dwelling pests.

- Staphylinidae (Rove Beetles) Targets: Aphids, mites, larvae of many insect pests, soil dwelling pests.

- Collops spp. (Collop beetle) Targets: Aphids, whiteflies, caterpillars, mealybugs, spider mites.

- Cantharidae (Soldier Beetles) Targets: Aphids, caterpillars, other soft-bodied insects.

- Cicindelinae (Tiger Beetles) Targets: Various insects and larvae.

- Cryptolaemus montrouzieri (Mealybug Destoyer) Targets: mealybug – the larva of this beetle looks like a mealybug while adult resembles a small beetle.

Lacewings (Chrysopidae)

Lacewing (Clemson University, Bugwood.org)

- Chrysoperla carnea (Common Green Lacewing) Targets: Aphids, whiteflies, thrips, small caterpillars, mites.

- Chrysoperla rufilabris (Southern Green Lacewing) Targets: Aphids, mites, thrips, whiteflies, small caterpillars.

Parasitic Wasps

Trichogramma Wasp (Victor Fursov, commons.wikimedia.org)

- Trichogramma spp. (typically called trichogramma wasp) Targets: Eggs of various moth and butterfly species (e.g., European corn borer, cotton bollworm)

- Aphidius colemani (no common name) Targets: Aphids (e.g., green peach aphid, melon aphid).

- Encarsia formosa (Whitefly Wasp) Targets: Whiteflies (e.g., greenhouse whitefly, sweet potato whitefly).

- Cotesia glomerata (Cabbage White Wasp) Targets: Caterpillars of the cabbage white butterfly.

- Gonatocerus triguttatus (known as Fairyflies sometimes) Targets: Glassy-winged Sharpshooter of grapes, spreader of Pierces Disease. May be hard to find!

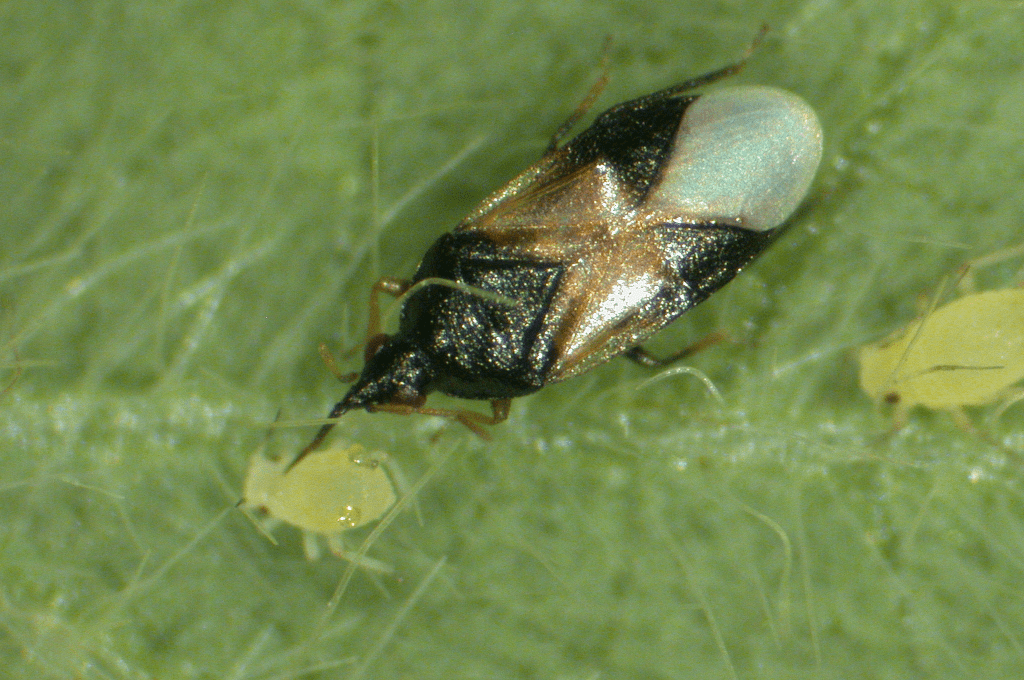

Pirate Bugs (Orius spp.)

Pirate bug. (Photo Credit: Ho Jung Yoo)

- Orius insidiosus (Minute Pirate Bug) Targets: Thrips: Both adult and larval stages, Aphids, Mites, Whiteflies, Psyllids, Caterpillars

- Orius majusculus Targets: Thrips: Both adult and larval stages, Aphids, Mites, Whiteflies, Psyllids, Caterpillars

- Orius tristicolor Targets: Thrips: Both adult and larval stages, Aphids, Mites, Whiteflies, Psyllids, Caterpillars

Hoverflies or Syrphid Flies

Hover Fly (Stephen Katovich, Bugwood.org)

- Episyrphus balteatus (Marmalade Hoverfly) Targets: Aphids, small caterpillars.

- Syrphus ribesii (Common Hoverfly or Ribbed Hoverfly) Targets: Aphids.

Predatory Mites (Phytoseiidae)

Phytoseiulus persimilis mite eating a Two-spotted spider mite!

- Phytoseiulus persimilis (no common name) Targets: Two-spotted spider mites, broad mites.

- Amblyseius swirskii (no common name) Targets: Thrips, whiteflies, spider mites.

- Neoseiulus cucumeris (no common name) Targets: Thrips, spider mites, broad mites.

Great video about mites and control of spider mites with Amblyseius swirskii

Predatory Nematodes

The Steinernema scapterisci insect-parasitic nematode in the juvenile phase can infect and kill insects in the Orthoptera order, such as grasshoppers and crickets. (Photo by David Cappaert, Bugwood.org.)

- Steinernema carpocapsae Targets: Cutworms, armyworms, webworms, cranefly larvae.

- Heterorhabditis bacteriophora Targets: Root weevils, white grubs, rootworms.

- Steinernema feltiae Targets: Fungus gnats, thrips, codling moth larvae, root maggots.

- Steinernema scapterisci Targets: Mole crickets, grasshoppers, crickets.

- Heterorhabditis bacteriophora Targets: Root weevils, white grubs, rootworms.

Where to Buy Beneficial Insects

Kunafin “The Insectary”

- https://www.kunafin.com/

- 13955 N Highway 277, Quemado, TX 78877

- Office: 830.757.1181 or 800.832.1113

- Email: office@kunafin.com

- Blaine Junfin

- Email: blaine@kunafin.com

- Cell: 210.262.6245

Koppert

- https://www.koppertus.com/

- Office: 800.928.8827

- Email: info@koppertonline.com

Beneficial Insectary (Biobest Group)

- https://insectary.com/

- Office: 800.477.3715 or 530.226.6300

- Email: info@insectary.com

Bioline AgroSciences

- https://www.biolineagrosciences.com/

- Office: 805.986.8265

- Tina Ziaei (North America West)

- tziaei@biolineagrosciences.com

- (778) 288-0462

- Ysidro Muñoz (North America West)

- ymunoz@biolineagrosciences.com

- (805) 666-9050

- Daryl Johnson (North America Midwest)

- djohnson@biolineagrosciences.com

- (551) 228-5979

- Nicolas Bertoni (North America East)

- nbertoni@biolineagrosciences.com

- (905) 714-6919

- Chris Daye (North America East)

- cdaye@biolineagrosciences.com

- (365) 323-4997

Applied Bionomics

- https://appliedbio-nomics.com/

- Email: info@appliedbio-nomics.com

- Go here to find a distributor

- https://appliedbio-nomics.com/find-a-distributor/

Arbico Organics

- https://www.arbico-organics.com/

- Office: 520.825.9785

BIOBEE

- https://biobee.us/

- Office: 410.572.4159

- Email: info@biobee.us

Tip Top Biocontrol

- https://tiptopbiocontrol.com/

- Email: sales@tiptopbio.com

- Office: 805.445.9001

Bugs for Growers

- https://bugsforgrowers.com/

- Office: 800.690.6233

Field Preparations

- Habitat Enhancement: Plant diverse flowering plants around the field to provide nectar and pollen for beneficial insects. Include cover crops and hedgerows to offer shelter and alternate food sources. Have available before purchasing beneficial insects.

- Minimize Pesticide Use: Avoid using broad spectrum organic pesticides that can harm beneficial insects. Many organic insect control products are specific to certain insects or insect systems (Pyganic will kill all beneficials although it is organic). Use targeted treatments if necessary and apply them at times when beneficial insects are less active.

- Create a Favorable Environment: Ensure the field has adequate moisture and avoid practices that disrupt the habitat of beneficial insects.

Beneficial Insect Delivery and Distribution Methods

Insect Delivery

Bulk Containers: Insects are often shipped in bulk containers containing a mixture of insects and a carrier medium (like vermiculite, bran, or buckwheat hulls).

Blister Packs: Small plastic blister packs containing a specific number of beneficial insects are used for easy handling and release.

Paper or Mesh Bags: Insects are placed in breathable bags that allow for easy distribution in the field.

Distribution Methods

Hand Release: Beneficial insects are manually sprinkled or shaken out onto the crops. Simple tools like a “saltshaker” or small containers can be used for more precise application. Used on smaller areas or targeted release points.

Mechanical Dispersal: Using blowers or air-assisted equipment to disperse insects over a larger area. Usually this means a specialized blowers designed for insect release, similar to leaf blowers but calibrated for the insects’ safety. Typically used on large-scale row crops where uniform distribution is necessary.

Aerial Release: Drones or small aircraft can be used to release insects over extensive fields. Drones equipped with special release mechanisms for even distribution and this method works great with very large fields or difficult-to-access areas.

Release Stations: Strategic placement of small containers or stations throughout the field that allow insects to disperse naturally. These are typically small cardboard or plastic tubes, blister packs placed on stakes or plants. These allow for continuous release over time and for mobile insects like predatory beetles or parasitic wasps.

Instructions for Applying Beneficial Insects in Fields

- Timing: Release beneficial insects early in the season before pest populations reach damaging levels.

- Quantity: Determine the appropriate release rate based on the specific crop and pest pressure. This information is often provided by suppliers of beneficial insects.

- Distribution: Distribute insects evenly across the field. Use dispersal devices like handheld blowers or distribute by hand in small release points throughout the crop area. Apply during cool, calm periods of the day, such as early morning or late afternoon, to minimize stress on the insects.

Specific Instructions for Different Beneficial Insects

- Lady Beetles

- Application: Release near aphid-infested plants. Ensure there is enough food and habitat for them to stay.

- Environment: Lady beetles prefer environments with flowering plants which provide nectar.

- Application: Release near aphid-infested plants. Ensure there is enough food and habitat for them to stay.

- Lacewings

- Application: Release lacewing eggs or larvae directly onto plants. Eggs can be scattered or placed on leaves.

- Environment: Favorable habitats include areas with nectar-producing plants to support adult lacewings.

- Parasitic Wasps (e.g., Trichogramma spp.)

- Application: Release near the time of pest egg laying. Attach release cards with parasitized eggs to plants or scatter loose eggs.

- Environment: Provide a mix of flowering plants to support adult wasps with nectar sources.

- Predatory Mites (e.g., Phytoseiulus persimilis)

- Application: Distribute mites onto plants where pest mites are present. Sachets or loose mites can be used.

- Environment: Ensure a humid environment, as mites require high humidity for survival.

- Predatory Nematodes (e.g., Steinernema spp.)

- Application: Mix nematodes with water and apply using irrigation systems, backpack sprayers, or watering cans.

- Environment: Keep soil moist for several days after application to ensure nematodes can move and infect pests.

Keeping Beneficial Insects in the Field

- Learn about your predator and be able to identify life stages. A Lacewing adult looks a lot different than the dragon-like nymph. The same is true for the Lady Beetle that has a ferocious looking larva!

- Avoid and pesticide applications after applying predators. Especially avoid using broad-spectrum pesticides that can harm beneficial insects. Even avoid irrigation applications, if possible, till predators can begin feeding.

- Regularly check pest and beneficial insect populations to assess the effectiveness of the release. Use sticky traps, visual inspections, and sweep nets for monitoring. Learn how effective your predators are and what the drop in pest insects looks like once predators are released.

- Maintain and promote a diverse habitat with cover crops and flowering plants to support beneficial insect populations. If is amazing how many pest insects stop in your predator habitat first and get eaten up!

- Minimize tillage to preserve the habitat of ground dwelling beneficial insects.

- Use trap crops to attract pests away from the main crop, allowing beneficial insects to control them more effectively.

Crop Varieties and Beneficial Insects

Selecting Varieties: Choose crop varieties that are known to attract and support beneficial insects. Some plant varieties may produce more nectar and pollen, which are crucial for the survival of beneficial insects.

Integrated Planting: Integrate flowering plants and companion plants that attract beneficial insects within the crop rows. This can be a way to better utilize waterways or sections of a pivot.

Real Life Example: In cotton fields, farmers can plant strips of alfalfa or clover, which attract lady beetles and lacewings. These beneficial insects will help control aphid populations, reducing the need for chemical interventions. Additionally, by maintaining a diverse plant environment, beneficial insects are more likely to stay and thrive in the field.

- Cotton Major Pest: Bollworm (Helicoverpa zea) Predator: Trichogramma spp. (parasitic wasp)

- Peanut Major Pest: Lesser Cornstalk Borer (Elasmopalpus lignosellus) Predator: Spined Soldier Bug (Podisus maculiventris)

- Corn Major Pest: European Corn Borer (Ostrinia nubilalis) Predator: Lacewing larvae (Chrysoperla spp.)

- Sorghum Major Pest: Sorghum Midge (Stenodiplosis sorghicola) Predator: Minute Pirate Bug (Orius insidiosus)

- Rice Major Pest: Rice Water Weevil (Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus) Predator: Ground Beetles (Carabidae family)

Great video on all kinds of beneficial insects!

Other Resources

- Organic Grain Storage Insect Control

- Biopesticides and Beneficial Insects Article

- Guidelines for Using Natural Enemies

- Scale Insects and Mealybugs – Winter/Spring is the time to look and treat!

- Biopesticides for the Control of Whiteflies

- Meet Amblyseius swirskii: a commonly used predatory mite in vegetable crops

- Beneficials and Biologicals: Two is Better than One

- Selecting a Variety for Your Farm

- Organic Rice Resources

- What is the True Cost of Compost (or manure) in 2024?

- Soil Testing, soil results, soil test labs

- Organic Fertilizer – what is it, what are the rules, and where do you buy it?

- Organic Materials/Products Lists

- Organic Weed Control

- Best Cover Crops for Weed Control and Fertility

- Allelopathy – What is it, what has it, and how do we use it?

- Organic Seed May Soon Be Required