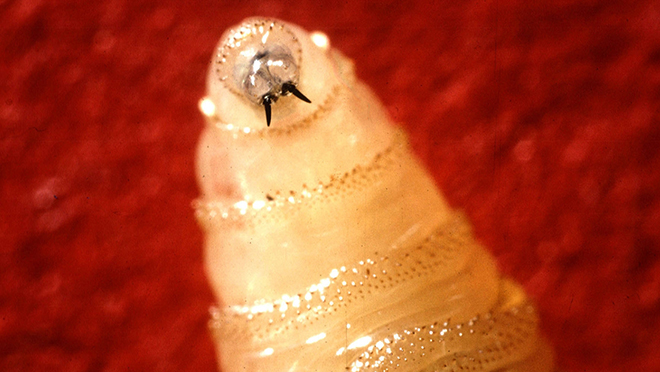

New World Screwworm (NWS, Cochliomyia hominivorax) is recognized as a highly destructive pest.¹,² NWS fly larvae, also known as maggots, invade the tissue of living animals, resulting in severe and often fatal injuries. This species can infest warm-blooded hosts, including livestock, pets, wildlife, humans, and even birds.²

Top and middle photos courtesy of CDC, bottom photo Marcy Ward, New Mexico State University.

The term “screwworm” is derived from the larvae’s characteristic feeding behavior, where they burrow into wounds in a manner like a screw penetrating wood.¹ Maggots inflict significant harm by tearing at host tissue with their sharp mouth hooks; consequently, the wound may enlarge and deepen as additional larvae hatch and feed on viable tissue.² The impact of NWS infestations can be substantial, frequently leading to life-threatening conditions for affected animals. Adult screwworm flies are comparable in size to common houseflies or slightly larger and are distinguished by orange eyes, metallic blue or green bodies, and three dark stripes along their backs.¹

Historically, screwworm caused severe economic losses in U.S. livestock production prior to eradication efforts, with annual losses estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars (mid-20th century values).⁴

USDA Strategy and Sterile Insect Technique

Central to eradication efforts is the sterile insect technique (SIT), a scientifically validated area-wide pest control method.⁵

Female NWS flies mate only once, so mating with a sterile male prevents reproduction and collapses the population over time.³,⁵ Sterile flies are released by air or ground, with aerial dispersal preferred for covering large areas. USDA produces sterile flies at the COPEG facility in Panama and is expanding domestic capacity at the Rio Grande Valley in Texas.¹

The sterile insect technique has been credited with the successful eradication of screwworm from the United States and much of Central America.³

Organic Considerations

For organic producers, livestock health care practices are governed under 7 CFR §205.238 of the National Organic Program regulations, which require preventive health care and prompt treatment of illness or injury.⁶

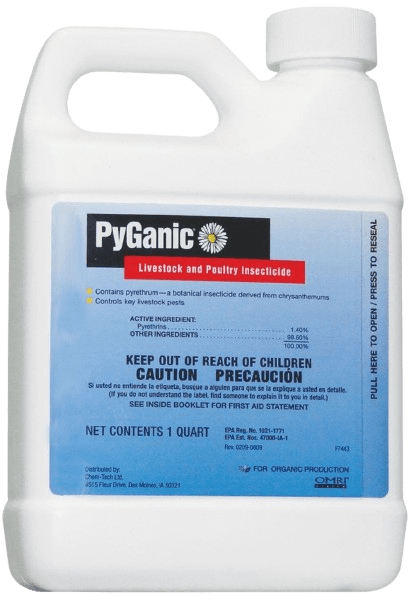

While APHIS provides guidance for detection and reporting,¹ there is very limited organic-specific direction currently available. Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) listings can be consulted to determine compliance of specific insecticides such as PyGanic Specialty.⁷ Typical insecticide suppression of New World screwworm is not highly effective because larvae infest wounds and wildlife hosts, so control relies primarily on detection, surveillance, and sterile male release rather than routine spray applications.⁴

PyGanic is a natural pyrethrum product labeled for livestock fly control and falls within the same broad insecticide class referenced in federal guidance for adult fly suppression. However, there are currently no published data evaluating PyGanic specifically against New World screwworm adults or larvae. Therefore, its potential role would be limited to adult fly suppression rather than eradication, and it should be considered as part of a broader management response rather than a stand-alone solution.

Producer Prevention and Reporting

Producers should:

- Monitor livestock closely for wounds or signs of infestation.¹

- Minimize injury risks by inspecting facilities and equipment.

- Treat livestock and potential wounds promptly with approved products. If wounds are infected with NWS then report and treat with approved products.

- Prevent introduction by controlling animal movement.

If screwworm is suspected, it must be reported immediately to State animal health officials and APHIS to enable rapid containment.¹

References

¹ USDA APHIS – New World Screwworm Information Page

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (n.d.). New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax). U.S. Department of Agriculture.

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/ticks/screwworm

² University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. (2025). New World screwworm: Cochliomyia hominivorax (Primary screwworm). EDIS Publication IN1146. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1146

³ Krafsur, E. S., Whitten, C. J., & Novy, J. E. (1987). Screwworm eradication in North and Central America. Parasitology Today, 3(5), 131–137.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15462936/

⁴ Texas A&M AgriLife Extension – New World Screwworm Fact Sheet

Phillip Kaufman, Sonja L. Swiger & Andy Herring. (2025). New World screwworm fact sheet. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service.

https://agrilifeextension.tamu.edu/new-world-screwworm-fact-sheet/

⁵ Sterile Insect Technique (Scientific Foundation)

Vreysen, M. J. B., Robinson, A. S., & Hendrichs, J. (Eds.). (2007). Area-wide control of insect pests: From research to field implementation. Springer.

https://www.iaea.org/topics/sterile-insect-technique

⁶ National Organic Program Regulation

Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. (2023). 7 CFR Part 205—National Organic Program.

https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-7/subtitle-B/chapter-I/subchapter-M/part-205

⁷ OMRI Listings

Organic Materials Review Institute. (n.d.). OMRI product search.

https://www.omri.org/omri-search