I am constantly asked about organic herbicides. I am tempted to shout back, “there are no organic herbicides!” Unfortunately, I would be wrong since the rules do allow for some “organic herbicide” use but overall, I AM RIGHT! The restrictions on using organic herbicides in a certified organic operation should and pretty much do eliminate their use. Here are some guidelines to consider.

Regulatory Framework (7 CFR §205)

The National Organic Program (NOP) requires that organic producers rely primarily on cultural, mechanical, and biological practices for weed control—not routine chemical herbicides. Synthetic substances are prohibited unless explicitly listed on the National List (7 CFR §205.600–607), and nonsynthetic (natural) materials are permitted only if they are not specifically prohibited in §205.602 and are included in guidance like NOP 5034‑1.

What Constitutes Allowed “Herbicides”

- Soap-based herbicides, which are naturally derived, are allowed—but only for limited situations such as farmstead maintenance, roadways, ditches, building perimeters, and ornamental plantings—not for use in food crop production Legal Information.

- Other natural herbicidal ingredients—acetic acid (vinegar), essential oils such as garlic or clove, corn gluten meal—may be formulated into commercial products (often OMRI-listed), but their use is still optional and must comply with producer’s approved Organic System Plan (OSP).

Why Use of Organic Herbicides Is Limited by the OSP

- The Organic System Plan (OSP) is mandatory and must list all substances used in operation. Certifiers evaluate this list, and only substances compliant with 7 CFR §205—including NOP guidance and National List—may be approved National List .

- Even when a natural herbicide is listed (e.g., an OMRI‑listed product), it must be justified as necessary. The NOP mandates that cultural, mechanical, and biological methods be used first. Only if these methods prove insufficient should pest, disease, or weed control materials—even those allowed—be considered.

Operational Examples

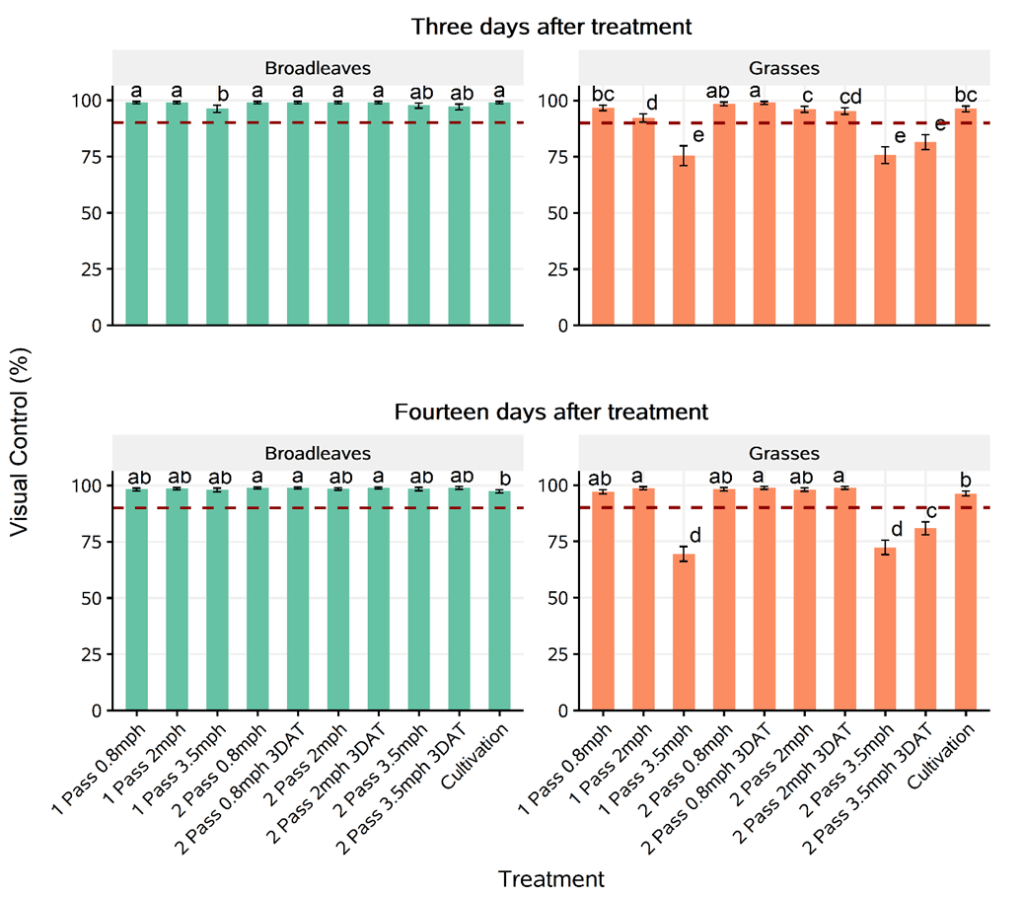

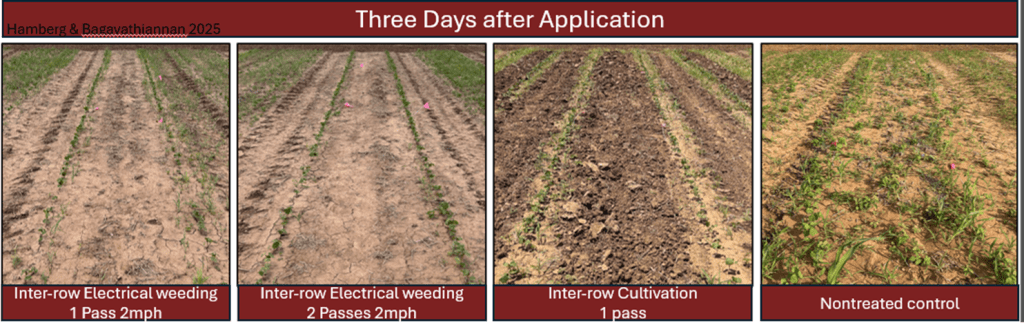

- A certified organic field might prioritize crop rotation, mulching, flame cultivation, inter-row mechanical cultivation, and cover cropping, with organic herbicide used only for spot treatment of particularly stubborn weeds—such as a few patches too difficult to manage manually. Typical examples are spraying organic herbicides around wellheads, pivot pads, fencerows, etc.

- Broad, wholesale use of even natural herbicides in food crop production would usually exceed what is allowable under the OSP. It could lead to certification issues or require pre-approval by the certifier. The general rule is to always check with your certifier but in this case your certifier is not going to allow you to use organic herbicides across your fields!

The Why — Benefits of This Restriction

- Preserves ecological balance: Overreliance on even natural herbicides can inadvertently harm non-target organisms like beneficial insects or soil microbes. Just imagine what a soap based, or acid based, or oil based organic herbicide would do to beneficial insects? Also, these organic herbicides do not discriminate – they will kill your crop along with the weeds.

- Resonates with organic principles: Organic agriculture emphasizes building soil health, biodiversity, and resilience—principles supported through non-chemical or even organic chemical approaches.

- Regulatory integrity: Standardizing allowable inputs assures consumers that “organic” means minimal allowable impact and reliance on natural systems rather than chemical solutions.

Summary Table

| Concept | Explanation |

| Organic Herbicides | Only certain types (e.g., soap-based) allowed and limited to non-food areas like roadways or ornamentals. |

| OSP Constraints | Materials must be listed and justified; broad use requires regulatory approval. |

| Order of Control Methods | Cultural → mechanical → biological → chemical (only if necessary). |

| Why Restricted | Ensures ecological integrity, respects organic philosophy, and upholds certification standards. |