by Ryan Hamberg – Graduate Research Assistant and PhD Candidate at Texas A&M University working in weed control research.

Inter-row cultivation is a “go-to” tool in organic production systems. However, repeated soil disturbance is bad for soil health, leading to erosion, organic matter loss, and more. Practices that maintain or enhance soil health are at the forefront of organic production systems. The problem is that few non-chemical tools exist to manage inter-row weeds organically without soil disturbance.

Figure 1. The Zasso inter-row electrical weeding prototype. (Left) The generator is located at the back of the tractor and the front applicator attachment. (Right) This unit is designed for small plot research and covers just two rows

Research is underway at the Texas A&M University Research Farm, where a “first-of-its-kind” prototype inter-row electrical weeder (EW) in cotton is being tested (Figure 1). This prototype unit was designed through collaboration with Zasso (Indaiatuba, Brazil) and purchased through the support of AgriLife Research and Cotton Incorporated. The prototype includes a large generator and transformer that is powered by the tractor PTO, with the applicator attached to the front loader (Figure 1). Many growers may already be familiar with the Weed Zapper or similar tools that can manage weeds present above the canopy (Figure 2). Though both technologies use electricity, this EW prototype uses a distinctly different delivery method and can kill weeds present between the rows, allowing for control of weeds present below the crop canopy.

Figure 2. A more common electrical weeder design that only targets weeds taller than the crop canopy.

Numerous experiments are currently being conducted to test this prototype unit to determine the feasibility of using this technology in organic row crops, including cotton. The study highlighted in this article aims to determine how EW compares to traditional cultivation methods. Treatments were applied at the early post-emergence timing, when cotton was at the 4-leaf stage. The treatment structure was as follows:

- One pass EW @ 0.8 mph

- Two-pass (double-knock) EW @ 0.8 mph – 2nd pass immediately after

- Two-pass (double-knock) EW @ 0.8 mph – 2nd pass 3 days after

- One pass EW @ 2 mph

- Two-pass (double-knock) EW @ 2 mph – 2nd pass immediately after

- Two-pass (double-knock) EW @ 2 mph – 2nd pass 3 days after

- One pass inter-row cultivation

- One pass EWC @ 3.5 mph

- Two-pass (double-knock) EW @ 3.5 mph – 2nd pass immediately after

- Two-pass (double-knock) EW @ 3.5 mph – 2nd pass 3 days after

- Nontreated control

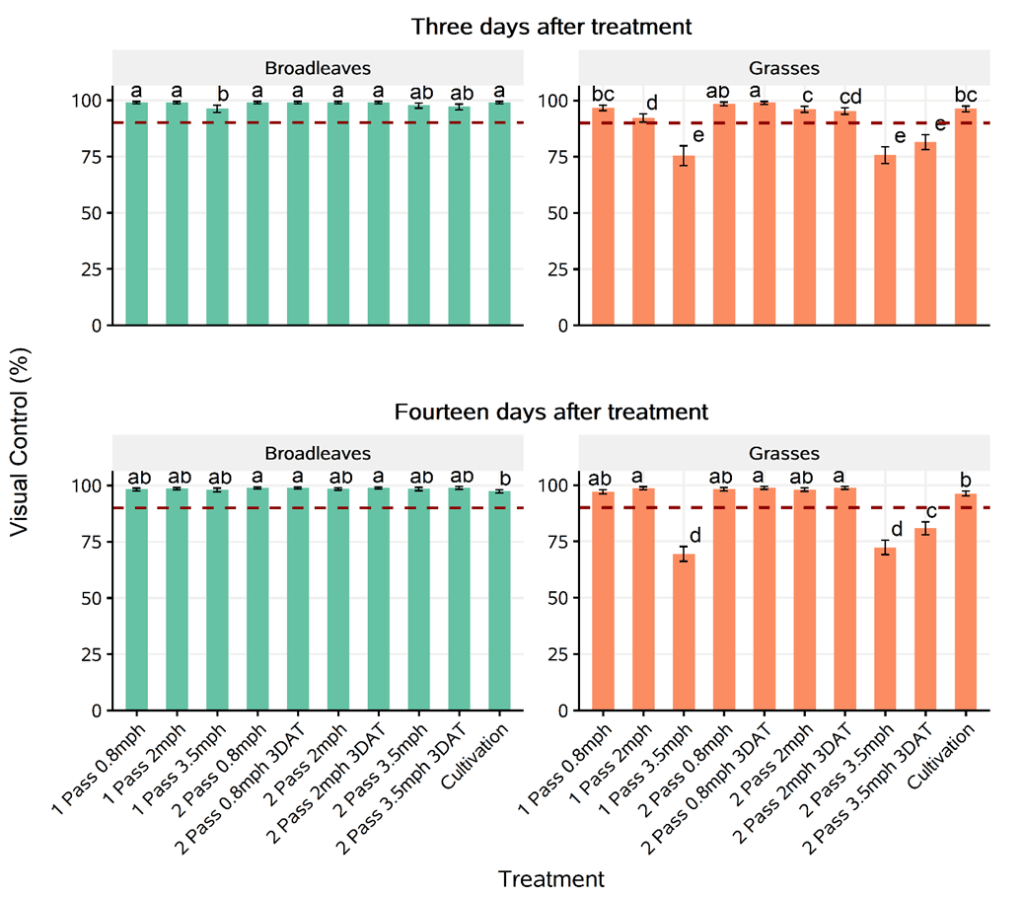

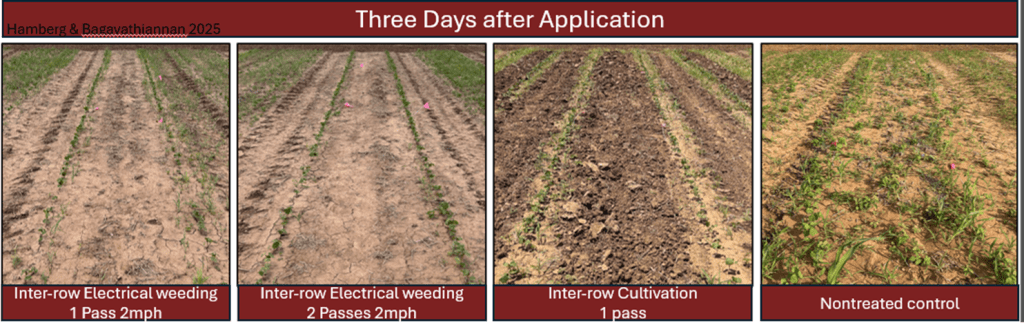

The field tested in this experiment was infested with hophornbeam copperleaf, ivyleaf morningglory, Palmer amaranth, Johnsongrass, and Texas panicum. Weeds ranged in height from 5 to 10 cm at the time of application. Between-row weed control was evaluated at 3 and 14 days after treatment (DAT). Broadleaf weed control exceeded 95% across all treatments at both evaluation timings (Figures 3 & 4). In general, electrical weeding performed comparably to cultivation for broadleaf control, except for a single pass at 3.5 mph. Control of grasses varied across treatments at both timings. Grass control at 0.8 and 2 mph was slightly higher (~ 3%) with two passes of EW compared to a single pass of cultivation. Electrical weeding at 3.5 mph reduced grass control to 70% with one pass. Even with two passes at 3.5 mph, control ranged from 74% to 81% (Figure 3). Some concerns over potential current transfer into crop roots were raised, and therefore, cotton injury was also assessed at 3 and 14 DAT. Cotton injury never exceeded 1% of the plot and was generally <1% overall (Data not shown). The cotton injury observed was always due to contact with the electrode of the EW and there was no indication that root transfer was occurring.

The present study indicates that inter-row EW holds promise as a non-chemical weed control option in row crop systems. The EW performed as well as inter-row cultivation on broadleaf weeds while minimizing soil disturbance. Reduced grass control at faster travel speeds suggests that slower applications are necessary when grass weeds are present. Previous research has found grasses as more tolerant to other thermal weed control tools such as flaming (Ulloa et al., 2010). Overall, the feasibility of the EW has been demonstrated. Ongoing and future research will assess the potential role of this tool within integrated weed management programs specifically designed for organic cropping systems.

Figure 3. Visual control ratings of broadleaf and grass weeds following electrical weeding at varying travel speeds compared to cultivation. The red dashed line represents the 90% control threshold.

Figure 4. Plots showing weed control treatments three days after application.

Discover more from Texas A&M AgriLife Organic

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.